Economic, financial and monetary developments

Overview

At its meeting on 6 March 2025, the Governing Council decided to lower the three key ECB interest rates by 25 basis points. In particular, the decision to lower the deposit facility rate – the rate through which the Governing Council steers the monetary policy stance – is based on its updated assessment of the inflation outlook, the dynamics of underlying inflation and the strength of monetary policy transmission.

The disinflation process is well on track. Inflation has continued to develop broadly as staff expected, and the March 2025 ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area closely align with the previous inflation outlook. Staff now see headline inflation averaging 2.3% in 2025, 1.9% in 2026 and 2.0% in 2027. The upward revision in headline inflation for 2025 reflects stronger energy price dynamics. For inflation excluding energy and food, staff project an average of 2.2% in 2025, 2.0% in 2026 and 1.9% in 2027.

Most measures of underlying inflation suggest that inflation will settle at around the Governing Council’s 2% medium-term target on a sustained basis. Domestic inflation remains high, mostly because wages and prices in certain sectors are still adjusting to the past inflation surge with a substantial delay. But wage growth is moderating as expected, and profits are partially buffering the impact on inflation.

Monetary policy is becoming meaningfully less restrictive, as the interest rate cuts are making new borrowing less expensive for firms and households and loan growth is picking up. At the same time, a headwind to the easing of financing conditions comes from past interest rate hikes still transmitting to the stock of credit, and lending remains subdued overall. The economy faces continued challenges and staff have again marked down their growth projections – to 0.9% for 2025, 1.2% for 2026 and 1.3% for 2027. The downward revisions for 2025 and 2026 reflect lower exports and ongoing weakness in investment, in part originating from high trade policy uncertainty as well as broader policy uncertainty. Rising real incomes and the gradually fading effects of past rate hikes remain the key drivers underpinning the expected pick-up in demand over time.

The Governing Council is determined to ensure that inflation stabilises sustainably at its 2% medium-term target. Especially in current conditions of rising uncertainty, it will follow a data-dependent and meeting-by-meeting approach to determining the appropriate monetary policy stance. In particular, the Governing Council’s interest rate decisions will be based on its assessment of the inflation outlook in light of the incoming economic and financial data, the dynamics of underlying inflation and the strength of monetary policy transmission. The Governing Council is not pre-committing to a particular rate path.

Economic activity

The euro area economy likely grew modestly in the fourth quarter of 2024. The first two months of 2025 saw a continuation of many of the previous year’s patterns. Manufacturing is still a drag on growth even if survey indicators are improving. High uncertainty, both at home and abroad, is holding back investment and competitiveness challenges are weighing on exports. At the same time, services are resilient. Moreover, rising household incomes and the robust labour market are supporting a gradual pick-up in consumption, although consumer confidence is still fragile and saving rates are high.

The unemployment rate stayed at its historical low of 6.2% in January 2025, and employment is estimated to have grown by 0.1% in the last quarter of 2024. However, demand for labour has moderated, and recent survey data suggest that employment growth was subdued in the first two months of 2025.

Persistently high geopolitical and policy uncertainty is expected to weigh on euro area economic growth, especially in investment and exports, slowing down the anticipated recovery. This follows slightly weaker than expected growth at the end of 2024. Both domestic and trade policy uncertainty are high. Although the baseline projection only includes the impact of new tariffs on trade between the United States and China, the negative effects of uncertainty regarding the possibility of further changes in global trade policies, particularly vis-à-vis the European Union, are assumed to weigh on euro area exports and investment. This, coupled with persistent competitiveness challenges, is assessed to lead to a further decline in the euro area’s export market share. Despite these headwinds, the conditions remain in place for euro area GDP growth to strengthen again over the projection horizon. Rising real wages and employment, in the context of a strong, albeit cooling, labour market, are expected to support a recovery in which consumption remains a key contributor to growth. Domestic demand should also be supported by an easing of financing conditions, as implied by market expectations about the future path of interest rates. The labour market should remain resilient, with the unemployment rate expected to average 6.3% in 2025, edging down to 6.2% in 2027. As some of the cyclical factors that have recently reduced productivity start to unwind, productivity is expected to pick up over the projection horizon, although structural challenges remain. Overall, annual average real GDP growth is expected to be 0.9% in 2025, and to strengthen to 1.2% in 2026 and to 1.3% in 2027. Compared with the December 2024 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, the outlook for GDP growth has been revised down by 0.2 percentage points for both 2025 and 2026, but is unchanged for 2027. The weaker outlook is mainly due to downward revisions to exports and, to a lesser extent, to investment, reflecting a stronger impact of uncertainty than previously assumed, as well as expectations that competitiveness challenges will likely persist for longer than had been anticipated.

Fiscal and structural policies should make the economy more productive, competitive and resilient. The European Commission’s Competitiveness Compass provides a concrete roadmap for action and its proposals should be swiftly adopted. Governments should ensure sustainable public finances in line with the EU’s economic governance framework and prioritise essential growth-enhancing structural reforms and strategic investment.

Inflation

According to Eurostat’s flash estimate, annual inflation stood at 2.4% in February 2025, after 2.5% in January and 2.4% in December 2024. Energy price inflation slowed to 0.2%, following a strong increase to 1.9% in January, from 0.1% in December. By contrast, food price inflation rose to 2.7%, from 2.3% in January and 2.6% in December. Goods inflation ticked up to 0.6%, while services inflation eased to 3.7%, from 3.9% in January and 4.0% in December.

Most indicators of underlying inflation are pointing to a sustained return of inflation to the Governing Council’s 2% medium-term target. Domestic inflation, which closely tracks services inflation, declined in January 2025. But it remains high, as wages and some services prices are still adjusting to the past inflation surge with a substantial delay. At the same time, recent wage negotiations point to a continued moderation in labour cost pressures.

Headline HICP inflation has increased over recent months but is projected to moderate marginally in the course of 2025 and then to decline and hover around the Governing Council’s inflation target of 2% from the first quarter of 2026. At the start of the projection horizon upward base effects in the energy component and higher food price inflation are expected to broadly offset downward impacts from a decline in HICP inflation excluding energy and food (HICPX). The rise in energy commodity prices at the turn of the year will carry over into the annual rate of change in energy prices in 2025. Although oil and gas prices are assumed to decline in line with futures prices, energy inflation is likely to continue to record positive rates, albeit below the historical average, over the entire projection horizon. In 2027 energy inflation is seen to be driven up by the introduction of new climate change mitigation measures. Food inflation is projected to rise until mid-2025, mainly driven by recent robust increases in food commodity prices, before declining to stand at an average of 2.2% in 2027. HICPX inflation is expected to start to decline in early 2025 as the effects of lagged repricing fade, wage pressures recede and the impact from past monetary policy tightening continues to feed through to consumer prices. The decline in HICPX inflation is expected to be mainly driven by a decrease in services inflation – which has thus far been relatively persistent. Overall, HICPX inflation is projected to moderate from 2.2% in 2025 to 1.9% in 2027. Wage growth should continue to follow a downward path from the current still elevated levels as inflation compensation pressures fade. Coupled with the anticipated recovery in productivity growth, this is expected to lead to significantly slower growth in unit labour costs. As a result, domestic price pressures are projected to continue to ease, with profit margins recovering over the projection horizon. External price pressures, as reflected in import prices, are expected to remain moderate assuming that EU trade tariff policies remain unchanged. Compared with the December 2024 projections, the outlook for headline HICP inflation has been revised up by 0.2 percentage points for 2025 on account of higher energy commodity price assumptions and the depreciation of the euro, while it has been marginally revised down for 2027 owing to a slightly weaker outlook for the energy component at the end of the horizon.

In summary, the assumption of higher energy price inflation led staff to revise up the headline inflation projection for 2025. At the same time, staff expect core inflation to continue slowing, as labour cost pressures ease further and the past monetary policy tightening continues to weigh on prices. Most measures of longer-term inflation expectations continue to stand at around 2%. All of these factors will support the sustainable return of inflation to the Governing Council’s target.

Risk assessment

The risks to economic growth remain tilted to the downside. An escalation in trade tensions would lower euro area growth by dampening exports and weakening the global economy. Ongoing uncertainty about global trade policies could drag investment down. Geopolitical tensions, such as Russia’s unjustified war against Ukraine and the tragic conflict in the Middle East, remain a major source of uncertainty as well. Growth could be lower if the lagged effects of monetary policy tightening last longer than expected. At the same time, growth could be higher if easier financing conditions and falling inflation allow domestic consumption and investment to rebound faster. An increase in defence and infrastructure spending could also add to growth.

Increasing friction in global trade is adding more uncertainty to the outlook for euro area inflation. A general escalation in trade tensions could see the euro depreciate and import costs rise, which would put upward pressure on inflation. At the same time, lower demand for euro area exports as a result of higher tariffs and a re-routing of exports into the euro area from countries with overcapacity would put downward pressure on inflation. Geopolitical tensions create two-sided inflation risks as regards energy markets, consumer confidence and business investment. Extreme weather events, and the unfolding climate crisis more broadly, could drive up food prices by more than expected. Inflation could turn out higher if wages or profits increase by more than expected. A boost in defence and infrastructure spending could also raise inflation through its effect on aggregate demand. But inflation might surprise on the downside if monetary policy dampens demand by more than expected.

Financial and monetary conditions

Market interest rates in the euro area decreased after the Governing Council’s meeting on 30 January 2025, but rose in the run-up to its meeting on 6 March in response to a revised outlook for fiscal policy. The interest rate cuts are gradually making it less expensive for firms and households to borrow and loan growth is picking up. At the same time, a headwind to the easing of financing conditions comes from past interest rate hikes still transmitting to the stock of credit, and lending remains subdued overall.

The average interest rate on new loans to firms declined to 4.2% in January 2025, from 4.4% in December 2024. By contrast, firms’ cost of issuing market-based debt rose to 3.7%, 0.2 percentage points above its December level. Over the same period, the average interest rate on new mortgages declined to 3.3%, from 3.4%.

Growth in bank lending to firms rose to 2.0% in January, up from 1.7% in December, on the back of a moderate monthly flow of new loans. Growth in debt securities issued by firms rose to 3.4% in annual terms. Mortgage lending continued to rise gradually but remained muted overall, with an annual growth rate of 1.3%.

Monetary policy decisions

The interest rates on the deposit facility, the main refinancing operations and the marginal lending facility were decreased to 2.50%, 2.65% and 2.90% respectively, with effect from 12 March 2025.

The asset purchase programme and pandemic emergency purchase programme portfolios are declining at a measured and predictable pace, as the Eurosystem no longer reinvests the principal payments from maturing securities.

Conclusion

At its meeting on 6 March 2025, the Governing Council decided to lower the three key ECB interest rates by 25 basis points. In particular, the decision to lower the deposit facility rate – the rate through which the Governing Council steers the monetary policy stance – is based on its updated assessment of the inflation outlook, the dynamics of underlying inflation and the strength of monetary policy transmission. The Governing Council is determined to ensure that inflation stabilises sustainably at its 2% medium-term target. Especially in current conditions of rising uncertainty, it will follow a data-dependent and meeting-by-meeting approach to determining the appropriate monetary policy stance. In particular, the Governing Council’s interest rate decisions will be based on its assessment of the inflation outlook in light of the incoming economic and financial data, the dynamics of underlying inflation and the strength of monetary policy transmission. The Governing Council is not pre-committing to a particular rate path.

In any case, the Governing Council stands ready to adjust all of its instruments within its mandate to ensure that inflation stabilises sustainably at its medium-term target and to preserve the smooth functioning of monetary policy transmission.

1 External environment

Over the review period from 30 January to 5 March, growth in global economic activity remained steady, although recent US trade policies imply stronger headwinds to come. Global trade growth moderated at the end of 2024, while US tariffs are putting existing trade networks at risk. The outlook for global growth and trade, as reflected in the March 2025 ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, has been revised downward due to recently implemented US tariffs and elevated trade policy uncertainty. Headline inflation across member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) increased slightly due to higher energy and food prices, while core inflation continued to decline. While headline inflation across major advanced and emerging market economies is still expected to decline gradually over the projection horizon (2025-27), headline inflation projections have been revised up for 2025 to reflect the pass-through of tariffs to consumer prices in the United States and, to a lesser extent, in China. Overall, recent US policy announcements add significant uncertainty to the outlook.

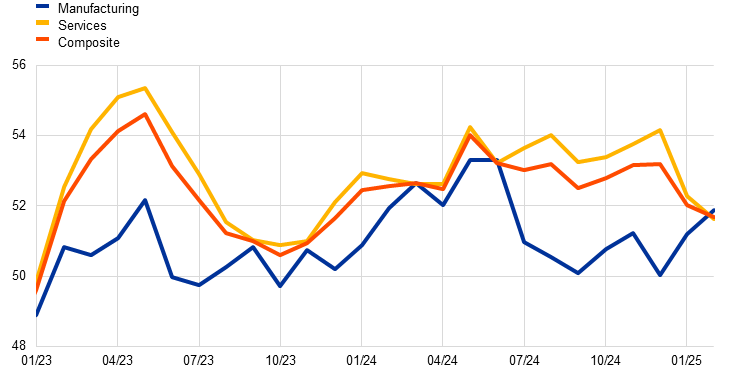

Growth in global activity remained steady at the turn of the year, but recent shifts in the US trade policy stance may imply stronger headwinds to come. Although still in expansionary territory, the global composite output Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) (excluding the euro area) declined in February 2025 due to a slowdown in the services sector (Chart 1), which had been the primary driver of growth in the second half of 2024. The drop in services sentiment was broad-based across major economies, but most pronounced in the United States. Overall, the latest ECB staff nowcasting model for global GDP, which incorporates a broad range of macroeconomic indicators in addition to PMIs, continues to point to steady growth of around 1.0% quarter-on-quarter in the first quarter of 2025. Nevertheless, near-term growth prospects are clouded by the recent changes to US trade policy, which implied not only the imposition of new tariffs on China but also an increase in trade policy uncertainty, which is expected to act as a drag on global investment.

Chart 1

Global output PMI (excluding the euro area)

(diffusion indices)

Sources: S&P Global Market Intelligence and ECB staff calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for February 2025.

The outlook for global activity growth is projected to remain moderate, easing slightly over the projection horizon. Global real GDP is projected to grow by 3.4% in 2025 before decreasing to 3.2% in 2026-27. While the precise timing and scope of recent US trade policy announcements are still unclear, the March 2025 ECB staff macroeconomic projections incorporate the tariffs imposed by the United States on imports from China – which came into force on 4 February (i.e. before the projections cut-off date of 19 February 2025) – and retaliatory measures by China.[1] Compared with the December 2024 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, global growth has been revised down by 0.1 percentage point for 2025 and 2026, as the newly imposed tariffs and higher trade policy uncertainty are expected to weigh on activity. In 2026-27, the slight decline in global GDP growth reflects slower growth in China amid unfavourable demographic dynamics, and in the United States due to the negative medium-term impact of US policies (e.g. lower immigration).[2] Downside risks to the global outlook prevail, driven by the threat of more US tariffs (e.g. levies on steel and aluminium, as well as tariffs on imports from Canada, Mexico and the European Union) and prevailing geopolitical tensions.

Global trade growth moderated at the end of 2024 and is projected to slow amid the impact of tariffs, elevated trade policy uncertainty, a less favourable composition of demand and an unwinding of the earlier frontloading of imports. While the mild improvement in manufacturing sentiment and industrial production can support global trade dynamics in the first quarter of 2025, growth in global activity at the turn of the year was driven mainly by components with low trade intensity, i.e. public and private consumption. In addition, elevated trade policy uncertainty and slower monetary policy easing in the United States are expected to weigh on investment in the future, affecting trade disproportionately as investment tends to be highly trade intensive. Moreover, the frontloading of trade – which supported global trade in 2024, as firms in the United States in particular stockpiled imports of foreign inputs ahead of possible trade disruptions – is expected to gradually fade in 2025 as new tariffs take effect. A partial unwinding of the frontloading of imports is also expected to weigh on demand throughout 2025, mostly across the advanced economies that frontloaded imports from emerging markets in 2024. Lastly, trade flows are expected to be significantly affected by tariffs over the projection horizon, with the March 2025 projections entailing large downward revisions to imports and exports in the United States and China by a cumulated 1.0-1.5 percentage points each over 2025-27. Against this background, growth in euro area foreign demand is projected to moderate from 3.4% in 2024 to 3.2% in 2025 and to 3.1% in 2026 and 2027, with significant downward revisions compared with the December 2024 projections.

The ongoing escalation of trade tensions poses risks to the smooth functioning of existing trade networks. The outlook for trade is clouded by uncertainty, as protectionism could significantly hamper cross-border flows. US tariffs on Canada and Mexico would affect around one-third of total US imports of goods and around three-quarters of total goods exported by Canada and Mexico, with the impact of tariffs likely to be amplified by the interconnected nature of supply chains across North America.[3] On 10 February, the US administration announced a 25% tariff on steel and aluminium entering the United States, effective as of 12 March.[4] Despite the small share of these goods in US imports (2%), US consumers and industries located downstream in supply chains (e.g. the automotive industry) are expected to be negatively affected. Furthermore, President Trump instructed his advisers to devise a comprehensive plan for reciprocal tariffs on 12 February, and announced global tariffs on cars, pharmaceuticals and semiconductors on 18 February. On 21 February he argued in favour of a review of trade partners’ tariffs on US digital services, announced a 25% tariff on European imports on 26 February and an additional 10% levy on China on 27 February.

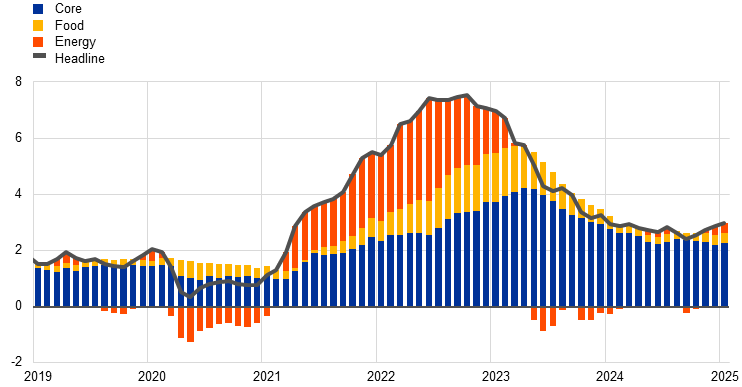

Headline inflation across OECD member countries has increased amid a slight increase in core inflation. In January 2025 the annual rate of consumer price index (CPI) inflation across OECD members (excluding Türkiye) rose to 3.0%, up from 2.9% the previous month (Chart 2). This uptick in headline CPI inflation was partly due to higher energy prices, with the contribution of food prices remaining broadly stable. Core CPI inflation, which excludes energy and food prices, increased slightly to 3.1%.

Chart 2

OECD CPI inflation

(year-on-year percentage changes, percentage point contributions)

Sources: OECD and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: The OECD aggregate excludes Türkiye and is calculated using OECD CPI annual weights. The latest observations are for January 2025.

Notwithstanding the recent uptick across OECD members, CPI inflation across a broader group of advanced and emerging countries is projected to remain on a declining path over the projection horizon. Although the disinflation process across OECD members appears to have stalled at the end of 2024, CPI inflation across a broader group of advanced and emerging countries in the March 2025 projections is expected to decline gradually from 4.2% in 2024 to 2.5% in 2027.[5] The cooling of labour markets across OECD members is expected to drive down nominal wage inflation, allowing headline CPI inflation to gradually converge towards central bank targets. Compared with the December 2024 projections, headline CPI inflation across a broader group of advanced and emerging countries is expected to be higher in 2025, reflecting the pass-through of tariffs to consumer prices in the United States and, to a lesser extent, in China. For 2026 and 2027, CPI inflation across global economies has been revised down, as the upward impact of tariffs is more than compensated by other factors, mainly downward revisions to CPI inflation in China, reflecting entrenched deflation in producer prices amid a lingering oversupply.

Over the review period, Brent crude oil prices decreased by 5%, while European gas prices declined by 12%. Concerns about the impact of trade disputes on global activity exerted downward pressure on oil prices, which was further reinforced by an unexpected build-up in US crude oil inventories, indicating weaker-than-expected demand for oil in the United States. European gas prices experienced strong volatility, as colder temperatures and a low renewable energy output led initially to higher prices owing to an increase in the amount of gas consumed for heating and to generate power. However, gas spot prices declined as a result of announcements about Ukraine peace negotiations. Downward price pressures have also been reinforced by milder weather and by LNG tankers being redirected towards Europe. Metal prices increased by 2%, mainly as a result of US-based traders making precautionary purchases following the announcements made on 10 February regarding steel and aluminium tariffs, along with threats made on 25 February to impose levies on imported copper. Lastly, food prices declined by 2%, as cocoa prices corrected downward slightly after surging in late 2024 and early 2025.

The March 2025 ECB staff projections foresee activity in the United States remaining solid in the near term led by strong growth in consumption, although risks from US policies are accumulating. Real GDP growth in the fourth quarter of 2024 (0.6% quarter-on-quarter) was mainly driven by private consumption owing to higher real disposable incomes, while business investment fell. In the first quarter of 2025 the latest ECB staff nowcast for US GDP expects growth to remain robust at 0.6% quarter-on-quarter. The financial constraints affecting US consumers appear to be growing, although the knock-on effects on consumption seem limited. While credit card defaults have risen to above their pre-pandemic averages, the number of consumer foreclosures and bankruptcies remains low by historical comparison, and the household debt service ratio remains close to pre-pandemic levels. In addition, the largest increase in credit card defaults relates to lower-income households, who account for only 12% of total consumer spending. On the nominal side, although the January CPI release was higher than expected, it hints at a decline in both headline and core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation in the near term, which is also supported by the recent deceleration in the producer price index (PPI). Overall, key sources of inflation are cooling in the United States, where labour market tightness indicators have steadily declined back to their pre-pandemic levels. Still, the inflation outlook remains subject to significant uncertainty, and US policies could further slow the gradual disinflation, as tariffs on US imports are expected to be passed through to consumer prices, while stricter immigration and deportations risk a renewed tightening of the labour market. Against this backdrop, US consumers have started to increase their short and long-term inflation expectations, which in turn may further slow the disinflationary process. Finally, the Federal Open Market Committee decided at its January meeting to keep the federal funds rate unchanged, signalling no hurry to adjust the interest rate, given the still robust economy.

The outlook for China is deteriorating, as domestic demand remains weak and exports are being hit by higher US tariffs. Following the pick-up in real GDP growth in the fourth quarter of 2024, latest indicators point to a slowdown in both manufacturing and services activity. A high frequency indicator for private consumption declined in January 2025, suggesting that the boost from previous fiscal support was short lived. Consumer confidence remains persistently negative, thus weighing on a broader spending recovery, with the main property market indicators also remaining sluggish. While new US tariffs are estimated to have a rather modest adverse impact on GDP growth, a further escalation of the US-China conflict implies downside risks, even though additional fiscal stimulus, which had already been signalled by Chinese authorities in December 2024, could mitigate this impact. Meanwhile, Chinese CPI inflation rose to 0.5% in January, while PPI inflation remained in negative territory at -2.3%. Core CPI inflation (excluding food and energy) increased slightly to 0.6% in January from 0.4% the previous month, mainly on account of a temporary increase in services prices following a pick-up in activity helped by increased fiscal support for consumption. Overall, sluggish domestic demand and overproduction are fuelling strong price competition among firms, implying subdued inflationary pressures over the medium term.

Activity in the United Kingdom remains modest amid persistent inflation. Real GDP grew modestly (0.1% quarter-on-quarter) in the fourth quarter of 2024, as private demand and net trade made negative contributions, which were partially offset by the positive impact from inventories and higher government spending. Weak short-term indicators for private demand suggest that subdued growth might continue into 2025. Headline CPI inflation rose to 3.0% in January 2025 from 2.5% in December 2024, driven mainly by food inflation. Headline CPI inflation is expected to remain elevated throughout 2025, supported by increases in energy prices and regulated price changes, as well as the impact of government policies announced in the Autumn Budget 2024 (e.g. an increase in the rate of employer National Insurance contributions). The Bank of England lowered the key policy rate by 25 basis points in its February meeting, judging that domestic price pressures remained stable and that the recent pick-up in headline CPI inflation will not lead to additional second-round effects on underlying domestic inflationary pressures.

2 Economic activity

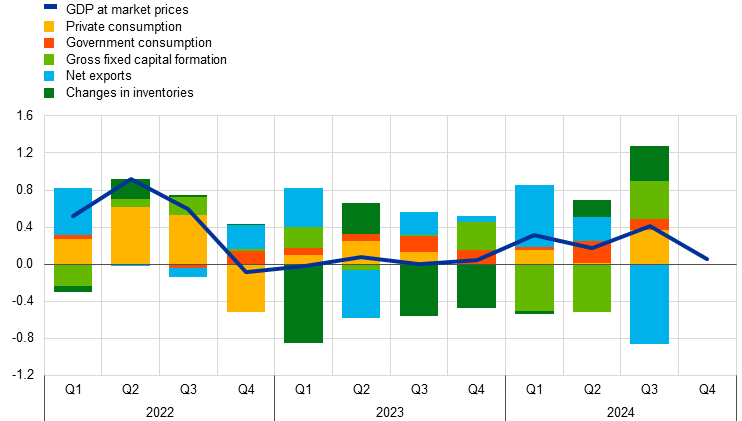

According to the information available at the cut-off date, the euro area economy grew by 0.1% in the fourth quarter of 2024, after expanding by 0.4% in the third quarter, amid increasing domestic demand and contracting exports. Employment rose by 0.1% in the fourth quarter, at the same pace as GDP. Across sectors, industrial activity is expected to have continued to decline in the fourth quarter, reflecting weak demand for goods, competitiveness losses and elevated uncertainty. By contrast, the services sector expanded further, boosted mainly by non-market services. Survey indicators point to moderate growth at the start of the year. The Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) for services has remained broadly stable vis-à-vis the fourth quarter, still indicating growth. At the same time, the manufacturing index, albeit continuing to indicate falling output, has recently improved. Further headwinds are likely to come from increasing protectionism and trade distorting measures, which might disproportionately affect the manufacturing sector compared with other parts of the economy. While the labour market has softened over recent months, it continues to be robust. Looking ahead, the high level of uncertainty and persisting competitiveness losses are expected to somewhat limit the speed of recovery of the euro area economy. Nonetheless, the projected recovery should be supported by higher labour incomes and more affordable credits.

This outlook is broadly reflected in the March 2025 ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, which foresee annual real GDP growth of 0.9% in 2025, 1.2% in 2026 and 1.3% in 2027.[6]

According to Eurostat’s flash estimate, real GDP edged up by 0.1%, quarter on quarter, in the fourth quarter of 2024 (Chart 3).[7] This means that output rose in all quarters of the year. As a result, GDP is estimated to have risen by 0.7% in 2024, which represents an improvement vis-à-vis 2023, when it grew by 0.4%.[8] Short-term indicators and available country data point to positive contributions from private consumption and investment, offset by falling net exports, while the contribution from changes in inventories was broadly neutral. At the same time, the industrial sector likely remained weak, while the services sector was more resilient. The fourth quarter outcome for the euro area generates a positive carry-over effect to annual growth in 2025.[9]

Chart 3

Euro area real GDP and its components

(quarter-on-quarter percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for the fourth quarter of 2024 for GDP and the third quarter of 2024 for the expenditure breakdown.

Survey data point to continued moderate services sector-led growth in the first quarter of 2025 amid elevated uncertainty. Uncertainty surrounding economic policy – including trade policy – is weighing on the near-term outlook. The predominant source of uncertainty on the global stage relates to US policies, particularly in the security and trade domains. Increasing protectionism might disproportionately affect the manufacturing sector compared with other parts of the economy. Nonetheless, the composite output Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) rose to 50.2 on average in January and February (from 49.3 in the fourth quarter), largely on the back of an increase in manufacturing. Despite this recent improvement, the manufacturing PMI still points to contracting activity, with the index having now been below 50 for almost two years (Chart 4). The PMI for new orders has also improved recently but still remains below 50, pointing to a weak short-term outlook for industry. In the services sector, the PMI remains above the no-growth threshold – although the latest readings have been below its long-term average. The European Commission’s business confidence indicators portray a broadly similar picture.

Chart 4

PMI indicators across sectors of the economy

a) Manufacturing | b) Services |

|---|---|

(diffusion indices) | (diffusion indices) |

|

|

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Note: The latest observations are for February 2025.

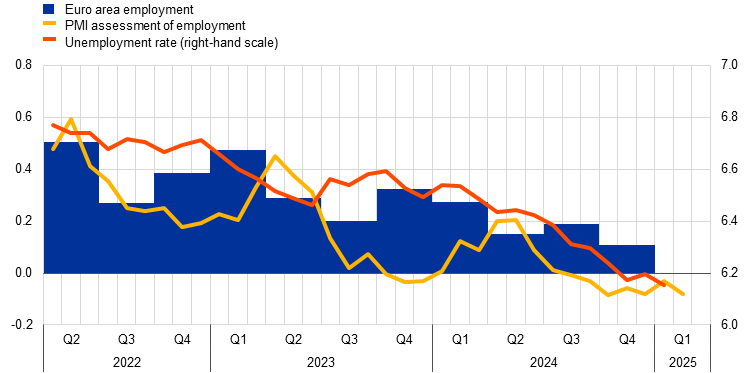

Employment increased by 0.1% in the fourth quarter of 2024. This was lower than in the other quarters of the year (Chart 5). Yet employment growth was resilient in relation to GDP growth, leading to a decline in productivity of 0.1%. The unemployment rate stood at 6.3% in December, 0.1 percentage points higher than in November, remaining close to its lowest level since the euro was introduced. Labour demand has declined somewhat from the high levels seen after the pandemic, with the job vacancy rate unchanged at 2.5% in the fourth quarter, 0.8 percentage points lower than its peak in the second quarter of 2022.[10]

Chart 5

Euro area employment, PMI assessment of employment and unemployment rate

(left-hand scale: quarter-on-quarter percentage changes, diffusion index; right-hand scale: percentages of the labour force)

Sources: Eurostat, S&P Global Market Intelligence and ECB calculations.

Notes: The two lines indicate monthly developments, while the bars show quarterly data. The PMI is expressed in terms of the deviation from 50, then divided by 10 to gauge the quarter-on-quarter employment growth. The latest observations are for the fourth quarter of 2024 for employment, February 2025 for the PMI assessment of employment and January 2025 for the unemployment rate.

Short-term labour market indicators point to stable employment in the first quarter of 2025. The monthly composite PMI employment indicator declined from 49.7 in January to 49.3 in February, suggesting that employment in the first quarter is likely to be broadly unchanged compared with the fourth quarter of 2024. The PMI employment indicator for services declined from 50.9 in January to 50.8 in February, while the PMI employment indicators for manufacturing and construction remained in contractionary territory.

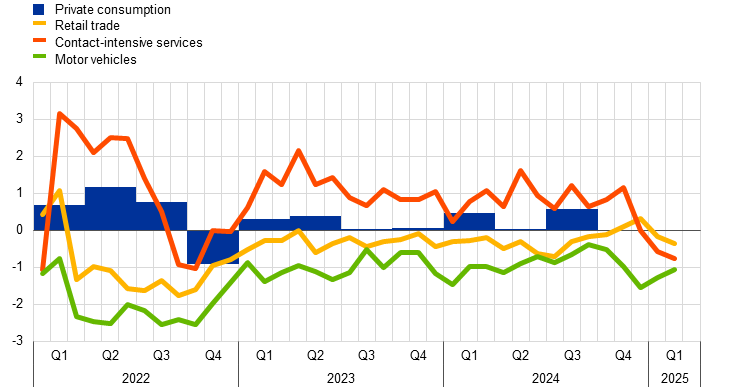

Private consumption growth likely moderated in the fourth quarter of 2024. After increasing by 0.7%, quarter on quarter, in the third quarter (Chart 6), private consumption growth seems to have moderated in the fourth quarter of 2024 – also reflecting the unwinding of some temporary factors that supported its expansion in the previous quarter, e.g. the Paris 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games. This is corroborated by the 0.4% quarter-on-quarter increase in retail sales and the 0.5% quarter-on-quarter rise in services production. Incoming data point to moderating momentum in household spending growth in the short term as well, as reflected in the latest ECB staff macroeconomic projections. The European Commission’s consumer confidence indicator edged up further in February but remains subdued overall, amid still high uncertainty. The European Commission’s indicators of business expectations for demand in contact-intensive services declined further in February, while the ECB’s latest Consumer Expectations Survey indicates that expected holiday purchases remain robust, despite some recent softening. At the same time, consumer expectations for major purchases in the next 12 months edged up in February, after deteriorating in the previous month. Going forward, persisting economic policy uncertainty, particularly in the context of global economic developments, should continue to weigh on households’ spending decisions. However, higher purchasing power – reflecting the slowdown in inflation – and continued rises in real labour income are expected to support consumption in the quarters ahead.

Chart 6

Private consumption and business expectations for retail trade, contact-intensive services and motor vehicles

(quarter-on-quarter percentage changes; standardised percentage balances)

Sources: Eurostat, European Commission and ECB calculations.

Notes: Business expectations for retail trade (excluding motor vehicles), expected demand for contact-intensive services and expected sales of motor vehicles refer to the next three months; “contact-intensive services” refers to accommodation, travel and food services. The contact-intensive services series is standardised for the period January 2005-19, owing to data availability, whereas motor vehicles and retail trade are standardised for the period 1999-2019. The latest observations are for the third quarter of 2024 for private consumption and February 2025 for business expectations for retail trade, contact-intensive services and motor vehicles.

Business investment likely remained muted around the turn of the year amid high uncertainty. Following the marked contraction in the third quarter of 2024, business investment (proxied in the national accounts by non-construction investment excluding Irish intangibles) is expected to have increased slightly in the fourth quarter. However, investment in tangible assets has been particularly weak over recent quarters. In the capital goods sector, industrial production fell by 1.2%, quarter on quarter, in the fourth quarter – as anticipated by the PMI output indicators diving deep into negative territory over the course of last year and the industrial confidence indicator at levels last seen during the 2020 lockdown (Chart 7, panel a). Intangible investment continues to grow, although well below the rates seen in the United States (see Box 1). Incoming data suggest weakness at the start of 2025 against a backdrop of elevated uncertainty surrounding geopolitical and economic policy as well as trade policy uncertainty. The latest Corporate Telephone Survey, the Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises in the euro area and the Bank Lending Survey all anticipate subdued investment at the start of the year, with the latter expecting a further downtick in demand in the first quarter for the longer-term loans typically associated with fixed investment.[11] These factors combined are likely to weigh on investment at the start of the year. Further ahead, barring strong disruptions to trade, the gradual pick-up in the wider economy, easing financing conditions and the resolution of some sources of uncertainty should support investment. In addition, ongoing deployments of Next Generation EU funds will help to further crowd in business investment.

Chart 7

Real investment dynamics and survey data

a) Business investment | b) Housing investment |

|---|---|

(quarter-on-quarter percentage changes; diffusion indices) | (quarter-on-quarter percentage changes; percentage balances and diffusion index) |

|  |

Sources: Eurostat, European Commission (EC), S&P Global Market Intelligence and ECB calculations.

Notes: Lines indicate monthly developments, while bars refer to quarterly data. The PMIs are expressed in terms of the deviation from 50. In panel a), business investment is measured by non-construction investment excluding Irish intangibles. Short-term indicators refer to the capital goods sector. The latest observations are for the third quarter of 2024 for business investment, January 2025 for the PMIs and February 2025 for industrial confidence. In panel b), the line for the European Commission’s activity trend indicator refers to the weighted average of the building and specialised construction sectors’ assessment of the trend in activity compared with the preceding three months, rescaled to have the same standard deviation as the PMI. The line for PMI output refers to housing activity. The latest observations are for the third quarter of 2024 for housing investment, January 2025 for PMI output and February 2025 for the European Commission’s activity trend.

Housing investment remained largely stable in the fourth quarter of 2024. After declining significantly from 2022 onwards, housing investment seems to have bottomed out in the fourth quarter of 2024, as available country data suggest a slight increase in housing investment in the fourth quarter, while production in building and specialised construction remained unchanged compared with the third quarter. Survey-based activity indicators improved at the beginning of this year. Yet overall they continue to point to muted momentum in housing investment in the first quarter of 2025, with both the PMI indicator for housing production and the European Commission’s indicator for building and specialised construction activity in the last three months remaining in contractionary territory (Chart 7, panel b). However, housing investment should gradually gain momentum as 2025 progresses. According to the European Commission’s survey, households’ short-term intentions to buy or build a house increased further in the first quarter. This improvement in sentiment is supported by falling mortgage rates and reflects a gradual recovery in housing loans, suggesting that housing demand is slowly increasing.

Euro area exports declined at a slower pace in the fourth quarter of 2024. Total extra-euro area exports contracted by 0.1%, quarter on quarter, in the fourth quarter. This decline confirms the persisting competitiveness challenges faced by euro area exporters (see Box 2), even amid a recovery in global demand. Looking ahead, surveys suggest that the performance of exports will continue to be subdued in the near term. The latest PMIs for new export orders remained well below the expansion threshold in February for both manufacturing and services. At the same time, monthly goods’ trade data suggest that quarterly import growth slowed in the fourth quarter, suggesting an overall negative contribution of net exports to GDP.

In the March 2025 projections the economic recovery is expected to be slower than anticipated in the December 2024 projections, while uncertainty has increased. According to the March 2025 ECB staff projections, the economy is expected to grow by 0.9% in 2025, 1.2% in 2026 and 1.3% in 2027. The downward revisions for 2025 and 2026 reflect lower exports and ongoing weakness in investment, in part originating from high trade policy uncertainty as well as broader policy uncertainty. Rising real incomes and the gradually fading effects of the past rate hikes remain the key drivers underpinning the expected pick-up in demand over time.

3 Prices and costs

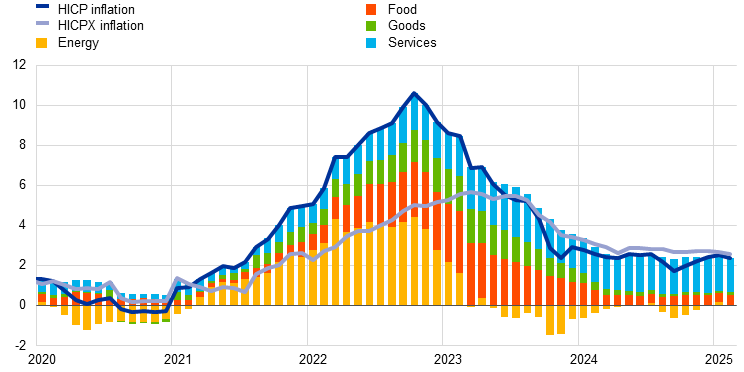

Euro area headline inflation decreased to 2.4% in February 2025, from 2.5% in January, primarily reflecting a decline in energy inflation. Food inflation increased while HICP inflation excluding energy and food (HICPX) edged down in February – concealing lower services inflation and higher non-energy industrial goods (NEIG) inflation. Most measures of underlying inflation suggest that it will settle at around the 2% medium-term target on a sustained basis. Wages and prices in certain sectors are still adjusting to the past inflation surge with a substantial delay, but wage growth is moderating as expected, and unit profit growth continues to partially buffer the impact of still elevated labour cost pressures on inflation. Most indicators of longer-term inflation expectations continue to stand at around 2%. Inflation has continued to develop broadly as staff expected and the latest projections closely align with the previous inflation outlook. The March 2025 ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area foresee headline inflation averaging 2.3% in 2025, 1.9% in 2026 and 2.0% in 2027. The upward revision in headline inflation for 2025 reflects stronger energy price dynamics.[12]

Euro area headline inflation, as measured by the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP), decreased to 2.4% in February from 2.5% in January (Chart 8). This was primarily attributable to an expected decline in energy inflation, which fell to 0.2% in February from 1.9% in January, owing mainly to a downward base effect and a month-on-month decline in energy prices. By contrast, food inflation stood at 2.7% in February, up from 2.3% in January, reflecting a higher annual rate for unprocessed food prices, while the rate for processed food prices was unchanged. The HICPX edged down to 2.6% in February from 2.7% in January – the first decline since September 2024. This reflected lower services inflation (at 3.7% in February, down from 3.9% in January) and concealed a small increase in NEIG inflation (0.6% in February, up from 0.5% in January). The decline in services inflation in February is in line with earlier expectations of both an initial moderation driven by gradually easing wage growth and weaker repricing effects in early 2025 than in 2024.

Chart 8

Headline inflation and its main components

(annual percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: “Goods” refers to non-energy industrial goods. The latest observations are for February 2025 (Eurostat’s flash estimate).

Most measures of underlying inflation are consistent with expectations that inflation will settle at around the 2% medium-term target on a sustained basis (Chart 9). In January 2025 – the latest month for which data are available – the bulk of the indicator values ranged from 2.1% to 2.8%. The Persistent and Common Component of Inflation (PCCI), which tends to perform best as a predictor of future headline inflation, was still at the bottom of this range, while the weighted median indicator increased to 2.8%. HICPX inflation excluding travel-related items, clothing and footwear (HICPXX) was unchanged at 2.6%, whereas the Supercore indicator, which comprises HICP items that are sensitive to the business cycle, decreased to 2.7%. Although the indicator for domestic inflation remained at a persistently high level, it edged down to 4.0% in January, from 4.2% in December 2024. This was the first time it had declined since October 2024. The change was due mainly to lower contributions from restaurant and cafe prices, as well as from insurance costs in the health and transport sectors.

Chart 9

Indicators of underlying inflation

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: The grey dashed line represents the ECB’s inflation target of 2% over the medium term. The latest observations are for February 2025 (Eurostat’s flash estimate) for HICPX, HICP excluding energy and HICP excluding unprocessed food and energy, and for January 2025 for all other indicators.

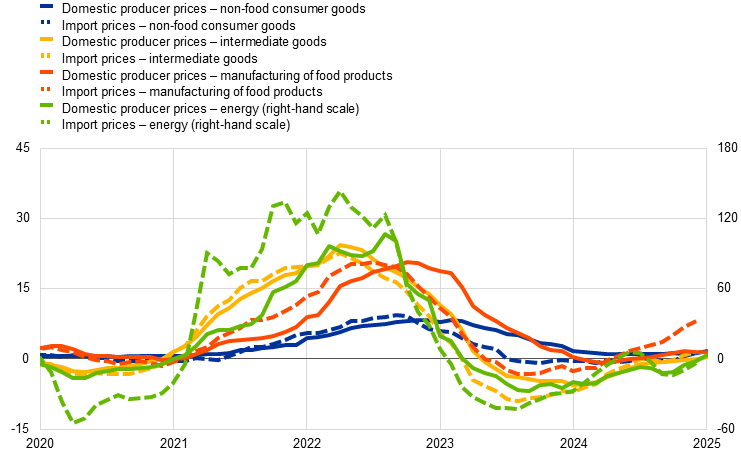

Most indicators of pipeline pressures for goods increased but at still moderate rates (Chart 10). At the early stages of the pricing chain, producer price inflation for energy, which had been negative since April 2023, turned positive, rising to 3.5% in January 2025 from ‑1.6% in December 2024. The annual growth rate of producer prices for domestic sales of intermediate goods increased (to 0.5% in January, up from 0.0% in December). At the later stages of the pricing chain, domestic producer price inflation for non-food consumer goods increased to 1.6% in January, from 1.2% in December, while producer prices for the manufacturing of food products decreased slightly to 1.4% in January, from 1.5% in December. The latest available data for import prices at the cut-off date for this report refer to December 2024. For intermediate goods, the annual growth rate of import prices had continued to rise (to 1.5% in December, up from 0.9% in November). Meanwhile, import price inflation for the manufacturing of food products had increased to 8.2% in December, possibly driven by the double-digit growth rates of international food commodity prices. The growth in import price inflation also reflects the depreciation of the euro. Overall, the latest data on producer and import prices confirm that the gradual easing of accumulated pipeline pressures on consumer goods has been fading out but has not resulted in a noticeable reacceleration.

Chart 10

Indicators of pipeline pressures

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for January 2025 for domestic producer prices and December 2024 for import prices.

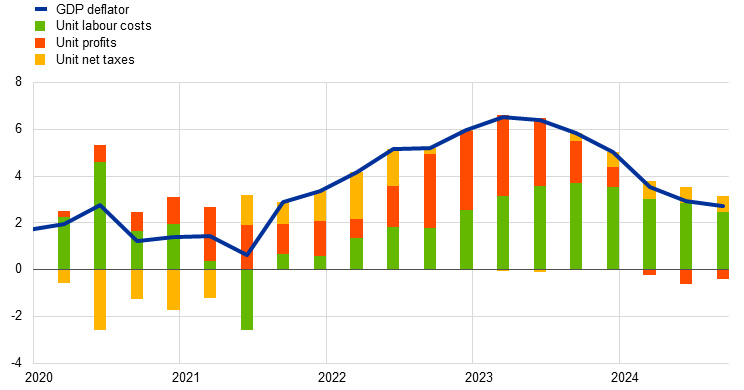

Domestic cost pressures, as measured by growth in the GDP deflator, fell further in the third quarter of 2024, although these remained elevated (Chart 11). The latest available national account data for domestic cost pressures for the euro area continue to refer to the third quarter of 2024. The annual growth rate of the GDP deflator declined to 2.7%, from 2.9% in the previous quarter, reflecting a smaller contribution from wages and unit labour costs. Unit profit growth remained in negative territory, indicating that it is continuing to buffer still elevated labour cost pressures. Available data from national accounts for most of the euro area countries suggested that the moderating labour cost growth and profit buffering continued in the fourth quarter. Moreover, other indicators available for the euro area in the fourth quarter, such as the labour cost index and the negotiated wage indicator, confirm the further easing of labour cost pressures. Growth in the hourly wages and salary component of the labour cost index declined to 4.1%, according to Eurostat’s flash estimate, from 4.4% in the third quarter. Growth in the negotiated wage indicator stood at 4.1% in the fourth quarter, down from 5.4% in the third quarter. Moreover, the ECB’s forward-looking wage tracker, which includes data on negotiated wage agreements up to mid-February, keeps pointing to easing wage growth pressures at the beginning of this year. Looking forward, the March 2025 ECB staff macroeconomic projections expect growth in compensation per employee to stand at 3.4% on average for 2025 and to continue moderating to 2.6% in 2027.

Chart 11

Breakdown of the GDP deflator

(annual percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: Compensation per employee contributes positively to changes in unit labour costs and labour productivity contributes negatively. The latest observations are for the third quarter of 2024.

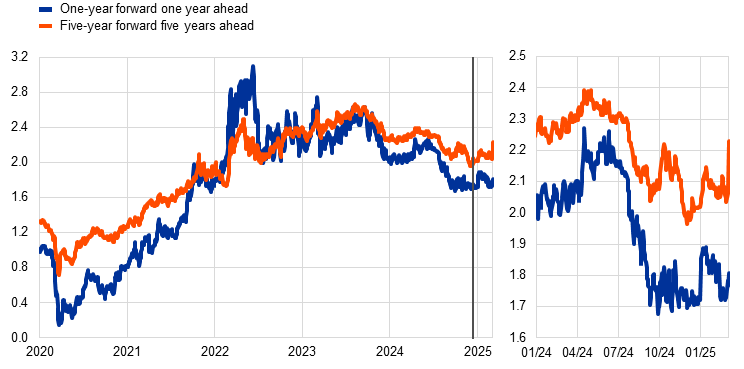

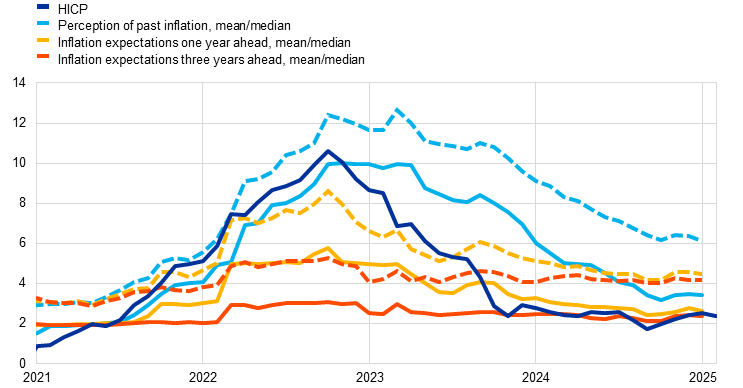

There was little change in survey-based indicators of longer-term inflation expectations, while market-based measures of medium to longer-term inflation compensation increased slightly, with most standing at around 2% (Chart 12). In both the ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters for the first quarter of 2025 and the ECB Survey of Monetary Analysts for March 2025, average and median longer-term inflation expectations remained at 2%. Shorter-term survey expectations for 2025 also stood at around 2% but saw small changes depending on the incorporation of the latest data outcomes and movements in energy commodity prices. Market-based measures of short-term inflation compensation, as measured by the one year forward inflation-linked swap rate one year ahead, have recently edged up and stand at around 1.8%. Looking at the medium and longer term, market-based measures of inflation compensation have also increased. Notably, the five-year forward inflation-linked swap rate five years ahead stands at around 2.2%, having increased by about 20 basis points since the December Governing Council meeting, largely reflecting movements following the recently announced plans for fiscal budget expansion in Europe. This rise is mostly attributed to higher inflation risk premia. Consequently, model-based estimates of genuine inflation expectations, excluding inflation risk premia, indicate that market participants continue to expect inflation to be around 2% in the longer term. On the consumer side, inflation expectations mostly resumed their downward momentum. According to the ECB Consumer Expectations Survey for January 2025, median expectations for headline inflation over the next 12 months decreased to 2.6%, from 2.8% in December 2024, while expectations for three years ahead remained unchanged at 2.4%. Median inflation perceptions over the previous 12 months declined slightly to 3.4% in January.

Chart 12

Market-based measures of inflation compensation and consumer inflation expectations

a) Market-based measures of inflation compensation

(annual percentage changes)

b) Headline HICP inflation and ECB Consumer Expectations Survey

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: LSEG, Eurostat, ECB Consumer Expectations Survey and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a) shows forward inflation-linked swap rates over different horizons for the euro area. The vertical grey line indicates the start of the review period on 12 December 2024. In panel b), the dashed lines show the mean rate and the solid lines the median rate. The latest observations are for 6 March 2025 for the forward rates, February 2025 (Eurostat’s flash estimate) for the HICP and January 2025 for all other measures.

The March 2025 ECB staff macroeconomic projections expect headline inflation to average 2.3% in 2025 and to decline to 1.9% in 2026 and 2.0% in 2027 (Chart 13). Headline inflation is projected to remain relatively stable in 2025, owing mainly to higher food inflation and base effects in energy prices, which broadly offset lower core inflation. It is then expected to gradually ease further in early 2026 as the base effects in energy inflation fade away. The projected increase in headline inflation in 2027 mainly reflects a temporary upward impact from energy inflation, owing to fiscal measures related to the climate change transition, in particular the introduction of a new Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS2). Compared with the December 2024 projections, the outlook for headline inflation has been revised up by 0.2 percentage points for 2025, is unrevised for 2026 and has been revised down by 0.1 percentage points for 2027. The upward revision for 2025 is mainly owing to upward data surprises for energy inflation and higher oil and electricity price assumptions. HICPX inflation is expected to decline from 2.8% in 2024 to 2.2% in 2025,2.0% in 2026 and 1.9% in 2027, primarily driven by a decrease in services inflation. Compared with the December 2024 projections, HICPX inflation has been revised down by 0.1 percentage points for 2025 and has been revised up by 0.1 percentage points for 2026.

Chart 13

Euro area HICP and HICPX inflation

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, March 2025.

Notes: The grey vertical line indicates the last quarter before the start of the projection horizon. The latest observations are for the fourth quarter of 2024 for the data and the fourth quarter of 2027 for the projections. The March 2025 ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area were finalised on 19 February 2025 and the cut-off date for the technical assumptions was 6 February 2025. Both historical and projected data for HICP and HICPX inflation are reported at a quarterly frequency.

4 Financial market developments

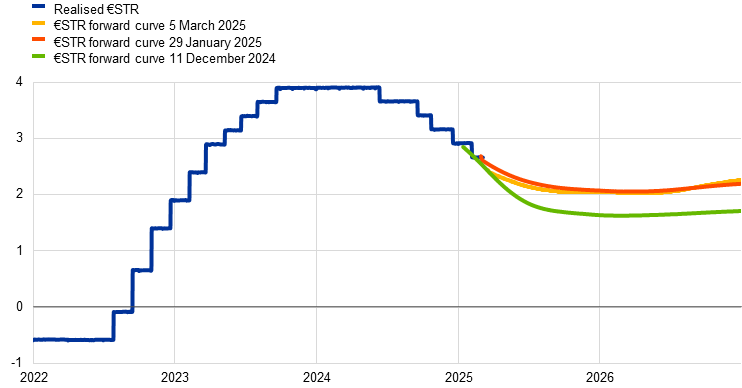

Over the review period from 12 December 2024 to 5 March 2025, the risk-free euro short-term rate (€STR) forward curve repriced upwards with significant intermittent fluctuations. Following the December Governing Council meeting, short-term interest rates increased across major advanced economies amid concerns that US disinflation was progressing more slowly than expected. After peaking in mid-January, the euro area curve retracted as markets anticipated a continuation of disinflation and a weaker growth outlook. However, it subsequently rebounded against the backdrop of defence and infrastructure spending plans in European countries. By the end of the review period, the euro area forward curve had priced in around 65 basis points of cumulative interest rate cuts by the end of 2025. Developments in euro area sovereign bond markets broadly tracked those in risk-free rates, with yield spreads relative to overnight index swap (OIS) rates widening somewhat. Despite the weak macroeconomic outlook and tariff announcements by the US Administration, euro area equity prices were shored up by a healthy earnings season, outperforming their US counterparts. Meanwhile, in euro area corporate bond markets, spreads narrowed for both investment-grade and high-yield issuers. In the foreign exchange market, the euro appreciated in trade-weighted terms and gained more substantially against the US dollar.

Since the December Governing Council meeting, the OIS forward curve has repriced upwards with significant intermittent fluctuations (Chart 14). The benchmark €STR averaged 2.8% over the review period, following the Governing Council’s widely anticipated decisions to lower the key ECB interest rates by 25 basis points at both its December and January meetings. Excess liquidity decreased by around €75 billion to €2,826 billion. This mainly reflected the repayments in December of funds borrowed in the third series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations and the decline in the portfolios of securities held for monetary policy purposes, with the Eurosystem no longer reinvesting the principal payments from maturing securities. The short end of the €STR-based OIS forward curve repriced upwards during the review period, pointing to a higher path for policy rates, with significant intermittent fluctuations. Following the December Governing Council meeting, short-term interest rates rose across major advanced economies amid concerns that US disinflation was progressing more slowly than expected. After peaking in mid-January, the euro area curve retracted as market participants anticipated a continuation of domestic disinflation and a weakening growth outlook, with the latter partly attributable to heightening trade uncertainty. However, in the run-up to the March Governing Council meeting, the euro area curve rebounded against the backdrop of defence and infrastructure spending plans in European countries. At the end of the review period, the forward curve fully priced in a rate cut of 25 basis points at the March Governing Council meeting and around 65 basis points of cumulative cuts by the end of 2025.

Chart 14

€STR forward rates

(percentages per annum)

Sources: Bloomberg and ECB calculations.

Note: The forward curve is estimated using spot OIS (€STR) rates.

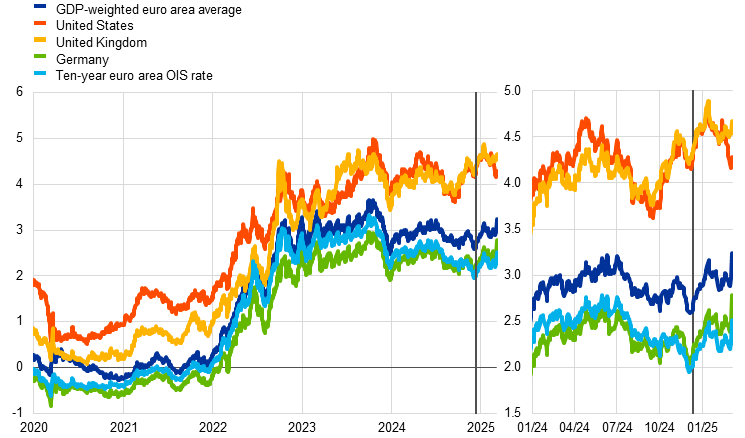

Euro area long-term risk-free rates fluctuated over the review period and increased overall (Chart 15). By the end of the review period, the ten-year euro area OIS rate had risen by around 45 basis points to approximately 2.5%, despite significant fluctuations throughout the period. The ten-year OIS rate climbed by around 40 basis points from the start of the review period up to mid-January on account of strong upward pressures originating from the United States. However, it subsequently retracted as market participants shifted their focus to the euro area outlook for inflation and the real economy. Finally, at the end of the review period, a ramp-up in fiscal spending plans in Europe caused long-term risk-free rates to increase by around 25 basis points. In the United States, long-term risk-free rates initially rose by around 45 basis points to reach their peak in mid-January, before falling from mid-February onwards. This retraction, which has recently been cemented by signs that US economic growth may be slowing, brought US rates down to around 4.3%, slightly below their levels at the beginning of the review period. As a result, the differential between ten-year risk-free rates in the euro area and the United States narrowed by 49 basis points. The ten-year UK sovereign bond yield increased by 31 basis points to stand at around 4.7% at the end of the review period.

Chart 15

Ten-year sovereign bond yields and the ten-year OIS rate based on the €STR

(percentages per annum)

Sources: LSEG and ECB calculations.

Notes: The vertical grey lines denote the start of the review period on 12 December 2024. The latest observations are for 5 March 2025.

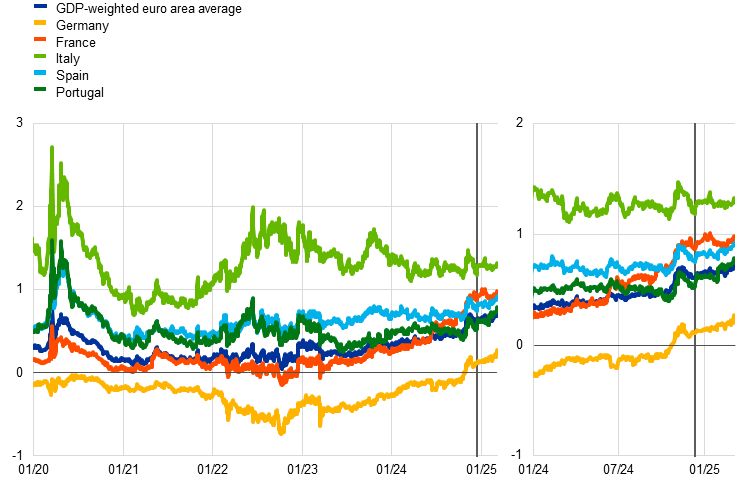

Long-term euro area sovereign bond yields generally tracked movements in risk-free rates, with some yield spreads widening (Chart 16). The ten-year GDP-weighted euro area sovereign bond yield closed the review period at around 3.2%, approximately 55 basis points higher than its level at the start of the period. This increase led to a widening of around 10 basis points in the spread over the €STR-based OIS rate. French sovereign bond yields performed similarly to the GDP-weighted euro area sovereign bond yield in spite of a recent perceived improvement in the country’s political situation following the French Parliament’s approval of the 2025 budget. The German sovereign bond spread widened by 16 basis points, remaining firmly in positive territory. Sovereign bond spreads also increased in other euro area countries, with Spanish and Portuguese sovereign bond spreads widening by 16 and 24 basis points respectively.

Chart 16

Ten-year euro area sovereign bond spreads vis-à-vis the ten-year OIS rate based on the €STR

(percentage points)

Sources: LSEG and ECB calculations.

Notes: The vertical grey lines denote the start of the review period on 12 December 2024. The latest observations are for 5 March 2025.

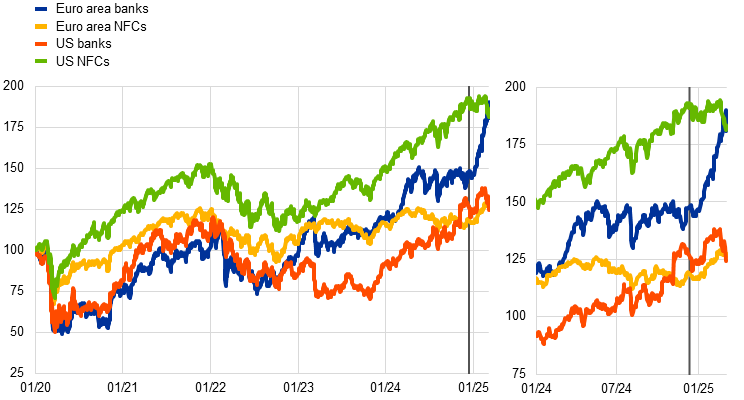

Euro area equity prices strengthened, propelled by a healthy earnings season despite the weak macroeconomic outlook and rising trade uncertainty (Chart 17). Over the review period, equity prices in the euro area climbed by 10.1% overall. Bank equity prices outperformed those of non-financial corporations (NFCs), with increases of 28.8% and 7.5% being recorded respectively. Euro area equity prices were supported by an ongoing healthy earnings season and by recently announced plans for fiscal budget expansion in Europe. Firms in the financial and industrial sectors reported particularly strong earnings relative to expectations and, consequently, they recorded some of the largest equity price gains. In the United States, the broad equity price index fell by 3.8% amid some recent concerns surrounding the US economic outlook and a decrease in IT-sector stock valuations as a result of perceived considerable advances in artificial intelligence in China. Notably, the equity prices of US NFCs declined by 4.4%, whereas those of banks fell by 1.2%.

Chart 17

Euro area and US equity price indices

(index: 1 January 2020 = 100)

Sources: LSEG and ECB calculations.

Notes: The vertical grey lines denote the start of the review period on 12 December 2024. The latest observations are for 5 March 2025.

Corporate bond spreads narrowed for high-yield and investment-grade firms, following movements in stock markets. The healthy earnings season was also reflected in corporate bond spreads, which declined in both the investment-grade and high-yield segments amid some volatility. Spreads on investment-grade corporate bonds narrowed by around 15 basis points, with spreads on bonds issued by financial corporations decreasing by less than those on non-financial corporate bonds. There was a more pronounced tightening of around 30 basis points in the high-yield segment, reflecting reductions in non-financial and financial corporate bond spreads of around 35 and 20 basis points respectively.

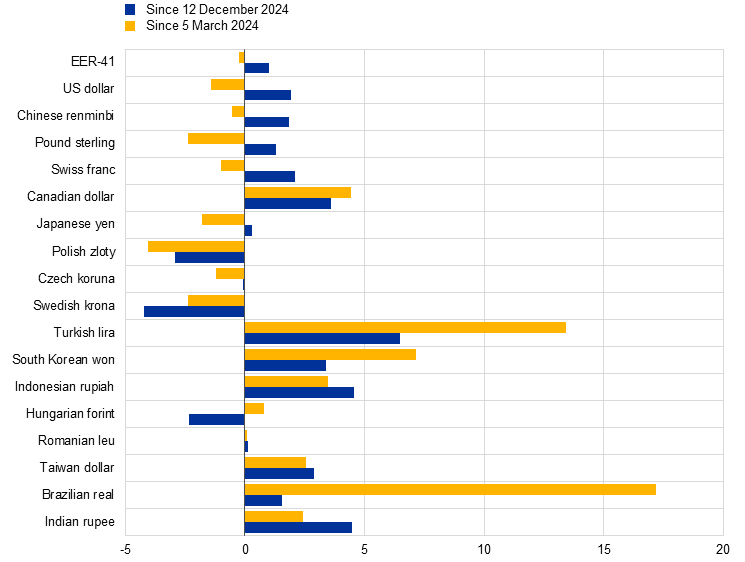

In foreign exchange markets, the euro appreciated in trade-weighted terms and strengthened to a greater extent against the US dollar (Chart 18). During the review period, the nominal effective exchange rate of the euro – as measured against the currencies of 41 of the euro area’s most important trading partners – strengthened by 1%. The euro appreciated by a significant 1.9% against the US dollar, following updates relating to Europe’s fiscal stance towards the end of the review period. The euro was also supported – albeit more modestly – by an overall increase in global risk appetite despite tariff announcements and some concerns over the US macroeconomic outlook, which were reflected in a decline in the interest rate differential between the United States and the euro area. The appreciation of the euro was fairly broad-based across currencies, significant fluctuations notwithstanding. Among the euro area’s largest trading partners, the euro appreciated against the pound sterling, the Indian rupee and the Turkish lira (by 1.3%, 4.5% and 6.5% respectively). It depreciated against the Polish zloty (by 2.9%), reflecting market participants’ expectations of a relatively tighter monetary policy stance in Poland, and against the Swedish krona (by 4.2%), partly on the back of narrowing expected interest rate differentials. The euro was broadly stable against the Japanese yen (+0.3%), as the impact of the Bank of Japan’s tighter monetary policy stance during the review period was offset by the increase in bond yields in the euro area.

Chart 18

Changes in the exchange rate of the euro vis-à-vis selected currencies

(percentage changes)

Source: ECB calculations.

Notes: EER-41 is the nominal effective exchange rate of the euro against the currencies of 41 of the euro area’s most important trading partners. A positive (negative) change corresponds to an appreciation (depreciation) of the euro. All changes have been calculated using the foreign exchange rates prevailing on 12 December 2024.

5 Financing conditions and credit developments

The ECB’s interest rate cuts are gradually making it less expensive for firms and households to borrow and loan growth is picking up. At the same time, a headwind to the easing of financing conditions comes from past interest rate hikes that are still transmitting to the stock of credit, and lending remains subdued overall. In January 2025 bank funding costs remained broadly unchanged at high levels, while bank lending rates continued their gradual decline from peak levels. The average interest rates on new loans to firms and on new mortgages fell in January to 4.2% and 3.3% respectively. Growth in loans to firms and households increased in January but remained weak and well below its historical average, reflecting still subdued demand and tight credit standards. Over the period from 12 December 2024 to 5 March 2025, the cost to firms of both equity and market-based debt financing increased owing to the higher long-term risk-free interest rate. The annual growth rate of broad money (M3) strengthened slightly to 3.6% in January.

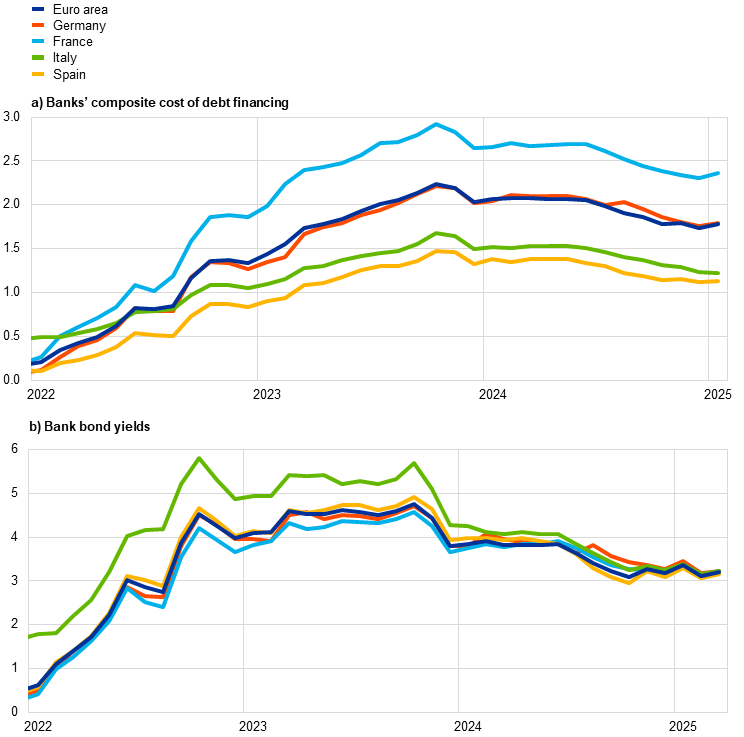

Euro area bank funding costs remained broadly unchanged in January 2025, despite past policy rate cuts. The composite cost of debt financing for euro area banks saw relatively little change in January (Chart 19, panel a). The upward pressure on bank funding costs resulted primarily from higher bank bond yields (Chart 19, panel b), driven by shifts in the long-term risk-free rate, as indicated by data available until 5 March. Average deposit rates remained fairly stable, with the composite deposit rate standing at 1.2% in January. While interest rates on time deposits for firms and households declined further, rates on overnight deposits and deposits redeemable at notice were unchanged overall.

Chart 19

Composite bank funding costs in selected euro area countries

(annual percentages)

Sources: ECB, S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and/or its affiliates, and ECB calculations.

Notes: Composite bank funding costs are a weighted average of the composite cost of deposits and unsecured market-based debt financing. The composite cost of deposits is calculated as an average of new business rates on overnight deposits, deposits with an agreed maturity and deposits redeemable at notice, weighted by their respective outstanding amounts. Bank bond yields are monthly averages for senior tranche bonds. The latest observations are for January 2025 for the composite cost of debt financing for banks (panel a) and for 5 March 2025 for bank bond yields (panel b).

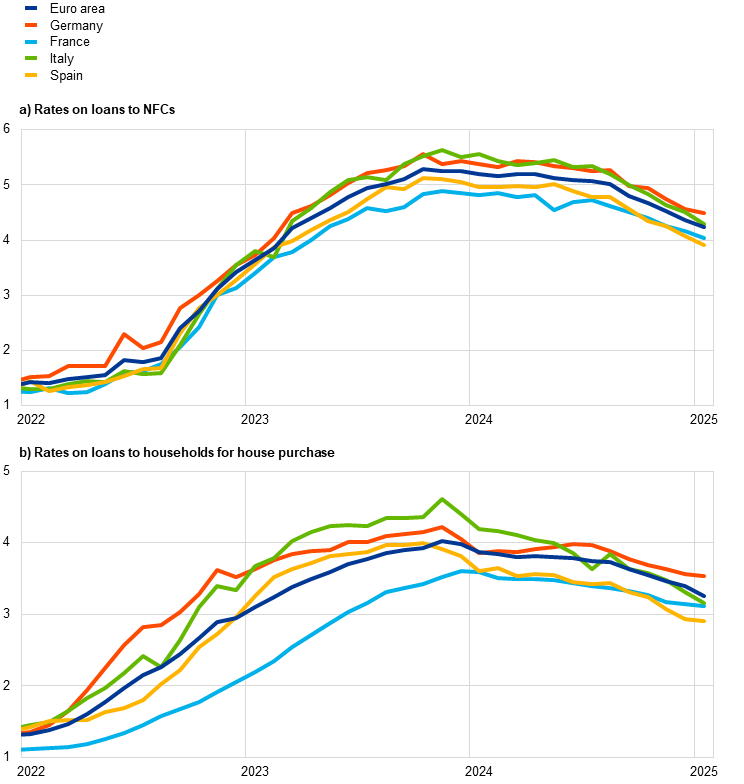

Bank lending rates for firms and for households declined further. Lending rates for firms and households have fallen since the summer of 2024, reflecting lower policy rates (Chart 20). In January 2025 lending rates for new loans to non-financial corporations (NFCs) fell by 12 basis points to stand at 4.24%, around 1 percentage point below their October 2023 peak (Chart 20, panel a). This fall was widespread across the largest euro area countries and concentrated in loans with maturities of up to five years. In contrast, rates on loans with maturities of more than five years increased by 11 basis points, reflecting the rise in longer-term risk-free rates. For firms, the cost of issuing market-based debt rose to 3.7% in January, 0.2 percentage points above its December level. The spread between interest rates on small and large loans to firms narrowed in January to 0.31 percentage points, close to its historical low, amid cross-country heterogeneity. Lending rates on new loans to households for house purchase edged down by 14 basis points to stand at 3.25% in November, around 80 basis points below their November 2023 peak (Chart 20, panel b), with variation across countries. The decline was driven solely by lower rates on renegotiated loans, while the rates on new loans excluding renegotiations were broadly unchanged.

Chart 20

Composite bank lending rates for firms and households in selected euro area countries

(annual percentages)

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: NFCs stands for non-financial corporations. Composite bank lending rates are calculated by aggregating short and long-term rates using a 24-month moving average of new business volumes. The latest observations are for January 2025.

Over the period from 12 December 2024 to 5 March 2025, the cost to firms of both equity and market-based debt financing rose. Based on the monthly data available until January 2025, the overall cost of financing for NFCs – i.e. the composite cost of bank borrowing, market-based debt and equity – declined in January compared with the previous month and stood at 5.6%, below the multi-year high reached in October 2023 (Chart 21).[13] Daily data covering the period from 12 December 2024 to 5 March 2025 show that the cost of market-based debt financing increased, driven by an upward shift in the overnight index swap (OIS) curve at the medium and long-term maturities that was only partially counterbalanced by a compression of corporate bond spreads associated with a healthy earnings season (see Section 4) that was more sizeable in the high-yield segment. The cost of equity financing rose as a result of the strengthening of the equity risk premium and – more notably – the higher long-term risk-free rate, as approximated by the ten-year OIS rate.

Chart 21

Nominal cost of external financing for euro area firms, broken down by component

(annual percentages)

Sources: ECB, Eurostat, Dealogic, Merrill Lynch, Bloomberg, LSEG and ECB calculations.

Notes: The overall cost of financing for non-financial corporations (NFCs) is based on monthly data and is calculated as a weighted average of the long and short-term cost of bank borrowing (monthly average data), market-based debt and equity (end-of-month data), based on their respective outstanding amounts. The latest observations are for 5 March 2025 for the cost of market-based debt and the cost of equity (daily data), and for January 2025 for the overall cost of financing and the cost of borrowing from banks (monthly data).

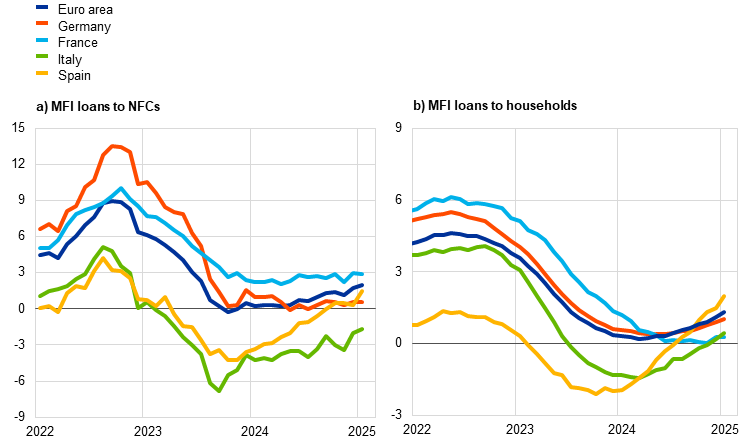

Growth in loans to firms and households increased in January but remained weak and well below its historical average, reflecting still subdued demand and tight credit standards. The annual growth rate of bank lending to firms rose to 2.0% in January 2025, amid volatile monthly flows, up from 1.7% in December 2024 but well below its historical average of 4.8% (Chart 22, panel a). The increase occurred despite a relatively weak monthly flow in January and was primarily attributable to base effects, given that the negative flow of January 2024 ceased to be included in the annual figure. Growth in debt securities issued by firms rose to 3.4% in annual terms. The annual growth rate of loans to households continued its steady recovery. It edged up to 1.3% in January from 1.1% in December, although it remained well below its historical average of 4.1% (Chart 22, panel b). Mortgages were still the primary driving force behind this upward trend, although consumer credit continued to strengthen, with its annual growth rising to 4.0% in January. By contrast, other lending to households, including loans to sole proprietors, was again weak. The ECB’s Consumer Expectations Survey in January showed that the percentage of households who perceived credit access to have been tighter still outweighs that perceiving credit access to have been easier.

Chart 22

MFI loans in selected euro area countries

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: Loans from monetary financial institutions (MFIs) are adjusted for loan sales and securitisation; in the case of non-financial corporations (NFCs), loans are also adjusted for notional cash pooling. The latest observations are for January 2025.

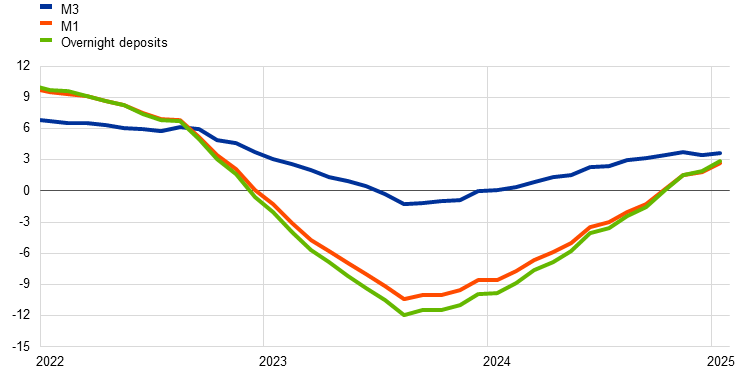

Broad money (M3) growth remained relatively stable in January, supported by bank purchases of government securities, while net foreign inflows continued to weaken. Annual M3 growth stood at 3.6% in January 2025, up from 3.4% in December 2024 but down from 3.8% in November (Chart 23). Annual growth of narrow money (M1) – which comprises the most liquid assets of M3 – increased to 2.7% in January, compared with 1.8% in December. The increase was driven by the sharp surge in the annual growth rate of overnight deposits, which rose to 2.9% in January, up from 1.8% in December, reflecting investors’ heightened preference for liquidity. The composition of money creation continued to shift. While the contribution of net foreign flows weakened further, bank net purchases of government securities picked up in January and the contribution of lending to firms and households gained weight, despite remaining subdued. At the same time, the ongoing contraction of the Eurosystem balance sheet and the increase in the issuance of long-term bank bonds (which are not included in M3) continued to contribute negatively to M3 growth.

Chart 23

M3, M1 and overnight deposits

(annual percentage changes, adjusted for seasonal and calendar effects)

Source: ECB.

Note: The latest observations are for January 2025.

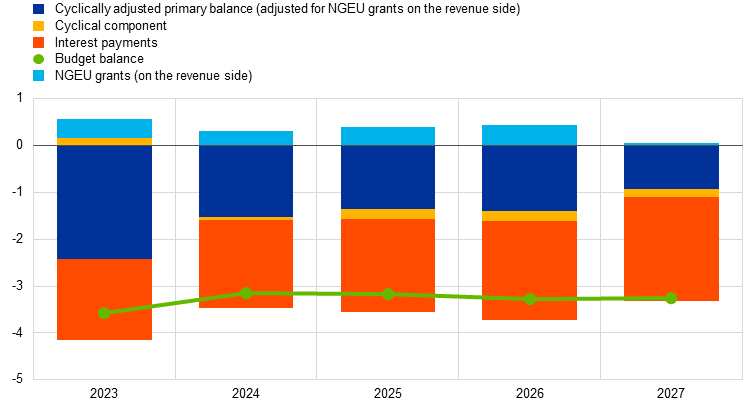

6 Fiscal developments

According to the March 2025 ECB staff macroeconomic projections, the euro area general government budget deficit is estimated to have declined to 3.2% of GDP in 2024 and expected to remain broadly unchanged until the end of the forecast horizon in 2027. The euro area fiscal stance is estimated to have tightened significantly in 2024 and a smaller tightening is also expected in 2025, mainly due to tax increases. While the fiscal stance is projected to be neutral in 2026, a relatively strong tightening is expected in 2027 when the Next Generation EU (NGEU) programme is set to expire. The euro area debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to increase slowly from an already elevated level and reach close to 90% in 2027. Governments should ensure sustainable public finances in line with the EU’s economic governance framework and prioritise essential growth-enhancing structural reforms and strategic investment. On 4 March 2025 the European Commission announced the ReArm Europe plan, outlining a set of proposals to use available financial levers to help EU Member States to quickly and significantly increase expenditures in defence capabilities.[14] The plan also includes making use of the flexibility in the revised economic governance framework, enabling Member States to act swiftly, as needed in the current situation.[15]

According to the March 2025 ECB staff macroeconomic projections, the euro area general government budget deficit should be unchanged at 3.2% of GDP in 2025 and remain broadly the same until 2027 (Chart 24).[16] The euro area budget deficit is estimated to have declined from 3.6% in 2023 to 3.2% of GDP in 2024, as a result of a combination of sizeable non-discretionary factors and the withdrawal of most of the energy and inflation support measures that were previously in place. The deficit should be unchanged at 3.2% in 2025 and remain broadly the same in the two following years as well, standing at 3.3% in both 2026 and 2027. The relatively stable outlook reflects a slow improvement in cyclically adjusted primary balances which is broadly offset by a gradual increase in interest expenditures. This increase reflects the pass-through of past interest rate rises, albeit proceeding at a slow pace given the long residual maturities of outstanding sovereign debt. Compared with the December 2024 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, the budget balance has been revised down very marginally for 2025 and more significantly by the end of the projection horizon (by 0.4 percentage points in 2027). These revisions primarily reflect a worsening of the macroeconomic outlook but also some fiscal loosening in discretionary fiscal measures.

Chart 24

Budget balance and its components

(percentages of GDP)

Sources: ECB calculations and ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, March 2025.

Note: The data refer to the aggregate general government sector of all 20 euro area countries.