Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 1/2025.

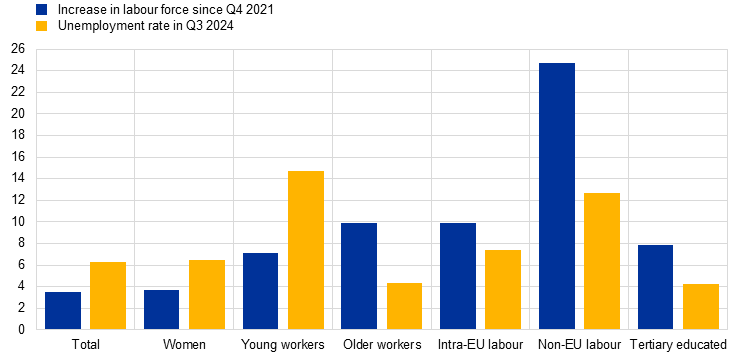

Demographic changes in the euro area labour market affect the unemployment rate. The euro area unemployment rate has decreased by 0.9 percentage points since the fourth quarter of 2021, falling to 6.3% in October 2024, its lowest level since the creation of the euro.[1] This decline occurred despite the significant increase in the size of the labour force, which grew by 3.5% between the fourth quarter of 2021 and the third quarter of 2024. This increase was largely attributable to non-EU labour[2], older workers[3] and workers with a tertiary education. These groups grew by 24.7%, 9.9% and 7.9% respectively (Chart A) and increased not only in terms of their respective sizes but also as regards their participation rates. The degree to which demographic shifts in the labour force can affect unemployment rates varies depending on the different characteristics of the groups concerned, including the differing unemployment risks of their professions and their job tenures. For instance, workers with longer job tenures often have greater protection against layoffs under employment legislation. Furthermore, experienced workers and workers with higher educational attainment levels frequently find new jobs more quickly after becoming unemployed. Demographic characteristics, such as age, educational attainment and nationality can therefore affect the likelihood of being employed or unemployed. Against this backdrop, this box explores the role of labour supply factors in driving the unemployment rate and, more specifically, the potential contributions of demographic developments.[4]

Chart A

Labour force participation and the unemployment rate by demographic group

(labour force: percentage changes; unemployment rate: percentages of the labour force)

Source: Eurostat.

Notes: The latest observations are for the third quarter of 2024. The unemployment rates and labour force figures have both been seasonally adjusted. The chart only shows those demographic groups with above-average labour force growth.

The number of unemployed has declined strongly in recent quarters. While the unemployment rate has been falling slowly since early 2023, the number of unemployed has diminished significantly, by some 1.0 million workers (8.7%), since the fourth quarter of 2021, equating to around 0.6% of the labour force over this period. Unemployment rates have, however, continued to vary significantly across demographic groups (Chart A). In the third quarter of 2024, the seasonally adjusted unemployment rates for older workers and for foreign workers (intra-EU and non-EU labour) stood at 4.4% and 12.7% respectively. Shifts in the demographic composition of the labour force may therefore also play a role in changes in the unemployment rate.

The fall in the unemployment rate has varied across demographic groups (Chart B, yellow bars). The unemployment rate decreased by 1.0 percentage points for women, but by just over 0.7 percentage points for men. A breakdown of the working population by nationality – national workers, intra-EU labour and non-EU labour – shows that the unemployment rate has fallen by 1.6 percentage points for non-EU labour since the fourth quarter of 2021, significantly more than the 1.2 percentage point decline seen for national workers over that period. The unemployment rate for intra-EU labour has only decreased by 0.8 percentage points over this period, reflecting their already lower unemployment rate. Across age groups, the sharpest decline in the unemployment rate has been for older workers. Major differences in the fall in the unemployment rate have also been observed across educational attainment groups, with the rate for workers with a non-tertiary education declining much more steeply than for workers with a tertiary education (‑ 1.1 and -0.3 percentage points respectively). Overall, this suggests that there is considerable variation in unemployment rate trends across demographic groups. The largest contributors to the fall in the unemployment rate are national workers and prime-aged workers (Chart B, blue bars), both of whom account for a large part of the labour force.

Chart B

Unemployment rate decomposition from the fourth quarter of 2021 to the third quarter of 2024

(percentage points)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: “Unemployment rate differential” is the change in the unemployment rates for each sub-group. "Proportion of the labour force” is the change in the contribution of each sub-group to the total labour force (adding up to zero across subgroups). "Contribution to changes in the unemployment rate” is the combined effect of the unemployment rate differential and the shift in the proportion of the corresponding demographic group in the labour force. The unemployment rates and labour force figures have both been seasonally adjusted. The latest observations are for the third quarter of 2024.

The decline in the unemployment rate has been supported by demographic shifts in the labour force. The rise in the proportion of older workers, non-EU labour and workers with a tertiary education in the labour force has intensified their contribution to the recent decline in the unemployment rate (Chart B, red bars). Over the last three years, the changes in the sizes of these groups have been substantial and accompanied by falling unemployment rates. These falls are attributable, first, to the constantly improving educational level of the workforce, reflecting better access to education in the euro area for the current cohorts relative to those of the past. The proportion of the workforce with a tertiary education has risen by 1.6 percentage points since the fourth quarter of 2021 (Chart B). Second, the proportion of older workers has increased strongly since 2021 (up by 1.3 percentage points), while the proportion of prime-age workers is continuing to decline (having fallen by 1.7 percentage points over the same period). Both groups contributed to the recent decline in the unemployment rate. Third, the proportion of foreign workers in the working population has also increased significantly over the past two years, particularly that of non-EU labour (rising by 1.3 percentage points since the fourth quarter of 2021). However, given that their unemployment rate is higher than that for the rest of the workforce, foreign workers did not contribute to the recent decline in the unemployment rate. Over the same period, the proportion of national workers decreased (falling by 1.6 percentage points since the fourth quarter of 2021) owing to the demographic decline in the working age of EU home-country populations.

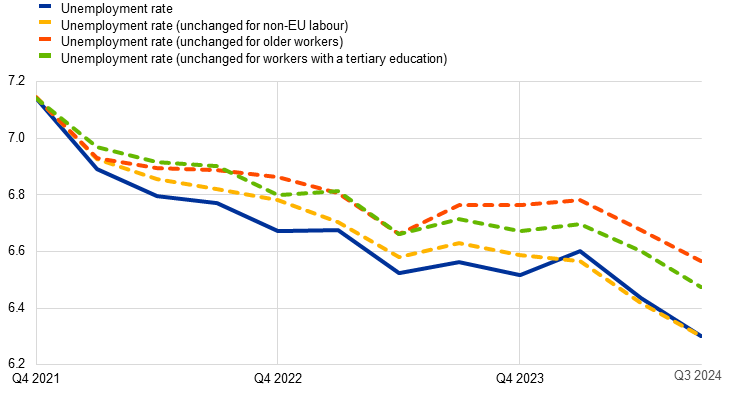

Most of the increase in the size of the labour force for foreign workers is reflected in higher employment, with the unemployment rate for such workers falling in line with that for national workers. Since the end of 2021, the participation of foreign workers in the labour market has risen significantly, increasing by 9.9% for intra-EU labour and by 24.7% for non-EU labour. While the unemployment rates for foreign workers (7.4% for intra-EU labour and 12.6% for non-EU labour) are significantly higher than the unemployment rate for national workers (5.8%), the growing participation of foreign workers in the labour market in recent years has had no significant impact on the unemployment rate in the euro area, given that much of this increased participation has translated into higher employment. The unemployment rate for non-EU labour has, in fact, fallen more than the rate for national workers. However, a counterfactual unemployment rate, assuming, for non-EU labour, an unchanged unemployment rate and labour force participation at the level observed in the fourth quarter of 2021, would not have changed the overall unemployment rate in the third quarter of 2024 and the rate would even have been 0.1 percentage points higher than in 2022-23 (Chart C).

Chart C

Unemployment rate and contribution of non-EU labour, workers with a tertiary education and older workers

(percentages of the labour force)

Source: Eurostat.

Notes: The unemployment rates and labour force figures for non-EU labour, workers with a tertiary education and older workers remain at their levels for the fourth quarter of 2021 in the counterfactual scenarios. The latest observations are for the third quarter of 2024. The unemployment rates and labour force figures have both been seasonally adjusted.

Shifts in educational attainment slightly decreased the unemployment rate. The increasing proportion of the workforce with a tertiary education contributed significantly to the gradual decline in the unemployment rate. If the proportions for educational attainment had remained at the levels seen in the fourth quarter of 2021, the unemployment rate in the third quarter of 2024 would have been 0.2 percentage points higher. While the unemployment rate for workers with a tertiary education did not fall more strongly than the overall rate, it was structurally lower. This can generally be explained by the more flexible skills of these workers, resulting in a reduction in their risks of unemployment and making it easier for them to find new employment after a job loss.[5] This is not the case in all countries, however. In Germany and the Netherlands, for instance, workers with a vocational secondary education have similar or even lower unemployment rates than workers with a tertiary education.

At the same time, the increasing proportion of older workers in the labour force has contributed significantly to the recent decrease in the unemployment rate. The population of the euro area is ageing and older workers are remaining in the labour market for longer. For instance, owing to their higher labour market attachment relative to previous cohorts and thanks to a continuing high demand for expertise and skills and a secular shift in tasks (e.g. towards less physically demanding tasks), more workers are continuing to work up to their statutory retirement age. Moreover, several countries have reformed their pension systems, leading to an increase in the effective retirement age.[6] Consequently, older workers are becoming a larger group within the labour force and their labour market participation increased by 9.1% between the fourth quarter of 2021 and the third quarter of 2024.[7] In addition, the unemployment rate for older workers is low, standing at 4.4% in the third quarter of 2024 (1.0 percentage points lower than in the last quarter of 2021), compared with 5.8% for prime-age workers (falling by 0.9 percentage points over the same period). If the unemployment rate and labour force participation of older workers had remained constant at the levels seen at the end of 2021, the aggregate euro area unemployment rate would have been 0.3 percentage points higher in the third quarter of 2024.

See the article entitled “Explaining the resilience of the euro area labour market between 2022 and 2024”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 8, ECB, 2024.

Throughout this box, “non-EU labour” is used to refer to workers who are not citizens of an EU country, “intra-EU labour” to workers who are citizens of an EU country but not of the country where they are working, and “foreign workers” to workers who are not citizens of the country in which they form part of the labour force. “National workers” refers to citizens of a euro area country working in that country.

For the purposes of this study, young workers are those in the 15-24 age group, prime-age workers are those in the 25-54 age group and older workers are those in the 55-74 age group.

The current dynamics of the unemployment rate have also benefited from labour hoarding in the euro area, which has helped to contain layoffs. For an analysis and estimates of labour hoarding, see the box entitled “Higher profit margins have helped firms hoard labour”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 4, ECB, 2024.

See, for example, Education at a Glance 2024: OECD Indicators, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris, 10 September 2024.

There is also a positive association between educational attainment and continued employment. See, for example, Venti, S. and Wise, D.A., “The Long Reach of Education: Early Retirement”, Journal of the Economics of Ageing, Vol. 6, 2015, pp. 1-13.

See Berson, C. and Botelho, V., “Record labour participation: workforce gets older, better educated and more female”, The ECB Blog, ECB, 8 November 2023; and the box entitled “Ageing cost projections – new evidence from the 2024 Ageing Report”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 5, ECB, 2024.