- SPEECH

Resilience offers a competitive advantage, especially in uncertain times

Keynote speech by Frank Elderson, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB and Vice-Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, at the Morgan Stanley European Financials Conference

London, 19 March 2025

We are living in unprecedented, turbulent times. Not a single week goes by without significant shifts in the global economy. We are seeing a surge in tariffs, an unravelling of global trade and a growing transatlantic divide leading to new geopolitical realities, all while wars continue right on our doorstep.

Meanwhile, the debate on financial regulation is also intensifying. Some have raised the question as to whether regulation and supervision have become too conservative that they may be hindering competitiveness. Perhaps some of the investors and bankers here in this room are asking themselves the very same question.

In my remarks today, I will highlight that, particularly in an era of heightened economic uncertainty and geopolitical shifts, we need competitive banks that ensure the flow of finance into investment and innovation. I will argue, however, that a vital pre-condition for banks to play their fundamentally important role of financing the real economy is that they remain resilient. Because a banking system that cannot withstand shocks cannot reliably finance the economy, especially when it matters most. And while there are merits in removing undue complexity from the regulatory framework without compromising resilience, the debate on competitiveness should not be used as a pretext for watering down regulation. Rather than reducing complexity by lowering regulatory requirements, it would be more effective to achieve simplification through European harmonisation: don’t cut rules, harmonise them.

Resilience of the European banking sector

Let me start with resilience. Over the past decade European banks have become significantly stronger. Thanks to robust regulatory guardrails and rigorous supervision, today’s banking sector is far more resilient than it was ten years ago. This is reflected in higher capital and liquidity buffers, improved risk management and better governance.

Euro area significant banks are currently in a good financial position, with the aggregate Common Equity Tier 1 ratio standing at 15.7% in the third quarter of 2024. Similarly, the leverage ratio stands comfortably above regulatory requirements at 5.8%. I anticipate that the data for the fourth quarter of 2024, due for release tomorrow, will confirm this overall trend.[1]

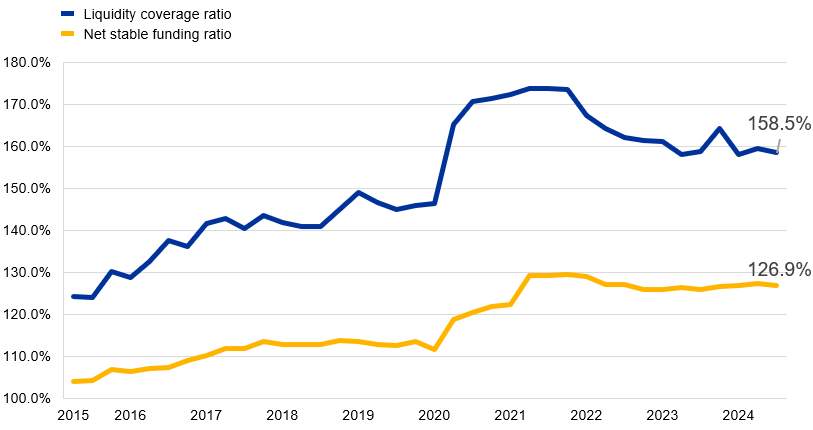

Liquidity ratios also remain well above regulatory requirements, with the liquidity coverage ratio standing at 158.5% and the net stable funding ratio at 126.9%.

Chart 2

Liquidity ratios

Source: ECB supervisory banking statistics and ECB internal computations for historical data.

This resilience is not a coincidence, but a testament to the joint efforts undertaken by regulators, supervisors and banks over the last decade.

It is worth remembering that the strong regulatory and pan-European supervisory framework was put in place as a response to the great financial crisis, which remains the biggest growth-destroying event in modern economic history.[2] The aim of legislators was clear: never again should we let excessive risk-taking, insufficient regulation and “light touch” supervision fuel another crisis like the one that affected millions of Europeans and resulted in average output losses of 8.5% of GDP in EU countries.

Encouragingly, Europe can look back on a decade of financial stability. Building on this renewed resilience, euro area banks are now in a much better position to support households and companies.

To ensure banks can continue to play this crucial role, their ability to earn sustainable profits is an indispensable component of resilience: without profits, banks cannot organically generate capital, make the necessary investment in future-proof IT systems, finance their clients’ growth projects and remain attractive to investors.[3] Encouragingly, the profitability of euro area significant banks has notably improved, with the aggregate annualised return on equity (RoE) standing at 10.2% in the third quarter of 2024. Despite this improvement, the positive effect of higher net interest income seems to have already peaked. Moreover, although banks have seen their return on equity increase, it is still barely higher than their own cost of equity estimates.[4] This shows that banks must keep a close eye on their operating efficiency.

Chart 3

Profitability: return on equity versus cost of equity

Source: ECB internal calculations.

Notes: This is the cost of equity as reported by the banks themselves. Owing to data availability constraints, the sample comprises a lower number of entities (104 significant institutions) than Supervisory banking statistics.

The European banking supervision cost of equity estimates (based on established methodologies) indicate a cost of equity which is normally higher than the self-reported cost of equity.

One possible way of improving operating efficiency would be to reap economies of scale. Scaling up would enable banks to arrive at the investment budgets they need for digitalisation and cybersecurity.

In a highly fragmented European banking system, these economies of scale could also be achieved through market consolidation. We have repeatedly stressed that from a supervisory perspective, we see benefits in cross-border mergers and will not stand in the way of consolidation. What matters is that the acquisition results in safe and sound banks, regardless of who the proposed acquirer is or whether it concerns a domestic or cross-border acquisition. Our supervisory assessment is limited to the prudential grounds and criteria laid down in a limitative manner in the law. This means ensuring that new entities resulting from business combinations have sustainable business models, comply with regulatory and supervisory requirements and have sound governance and risk management arrangements in place.[5] Back in 2021, to be as transparent as possible about our approach for the benefit of market participants, we published a guide to consolidation in the banking sector clearly setting out our supervisory expectations.

Risk outlook

Resilience must, however, not lead to complacency. The risk environment is changing in ways that demand our continued vigilance.

Although euro area GDP growth improved slightly to 0.7% in 2024, it remains subdued. In addition to the risks to the GDP outlook being tilted to the downside, structural trends are developing that may cause significant bottlenecks in global and European economies in the period ahead.[6]

For example, geopolitical tensions are not expected to subside, we are seeing economic fragmentation along geopolitical fault lines and protectionist measures are growing. And while all of this is happening, the climate and nature crises – although lately it seems less fashionable in certain circles to point out this undeniable fact – are getting worse, and natural disasters are becoming ever more frequent, severe and costly.[7]

The macro-financial context is having an impact on both the financial and non-financial risks that banks are facing.

Let me start by looking at the financial risks, focusing first of all on credit risk. Currently, the non-performing loan (NPL) ratio stands close to historical lows at 2.3%. However, corporate insolvencies are on the rise, potentially leading to higher credit risk. Moreover, downside risks may materialise in sectors that are particularly sensitive to current macroeconomic trends.

Chart 4

Asset quality: NPL ratio

Source: ECB supervisory banking statistics

Note: “cb” refers to “cash balances at central banks and other demand deposits”.

In fact, we can see early signs of weakening asset quality, particularly in vulnerable sectors, such as commercial real estate, and in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Worryingly, banks’ provisions do not appear to sufficiently reflect downside risks, confirming some persistent shortcomings in their International Financial Reporting Standard 9 (IFRS 9) provisioning frameworks.

Against this backdrop, European banking supervision made banks’ credit risk management one of its key supervisory priorities for 2025-27, spurring on banks to pay close attention to the bread and butter task of sound credit risk management.

For example, this means that instead of kicking the can down the road, banks should recognise deteriorations in asset quality in a timely manner and ensure their provisioning develops in lockstep with decreasing asset quality.

Banks are also advised to identify borrowers that may experience structural repayment difficulties in sectors of the economy that are particularly sensitive to current macroeconomic trends. That is also why we are continuing our supervisory work on vulnerable sectors, by focusing for instance on banks’ preparedness in dealing with potential economic deterioration across the full value chain of the automotive sector.

Moving on to non-financial risks, let me stress that – especially in the current risk environment – strong governance and sound risk culture are crucially important.[8] Banks’ management bodies must ensure the effective and prudent management of their bank[9], and are therefore ultimately responsible for ensuring that banks are prepared for the challenges of today’s risk landscape.

However, good governance, financial resilience and sound risk management are essential but not enough in themselves to ensure that banks always remain at the service of the economy. To do so, they must also be operationally resilient. Why is that?

Let’s take the example of Amsterdam Trade Bank (ATB), which filed for bankruptcy even though it had ample capital and liquidity. What went wrong? Due to sanctions, ATB had lost access to its IT systems, which were run by third-party providers. There were no adequate contingency arrangements in place, so this well-capitalised, liquid, but operationally insufficiently resilient bank had to close.

Another example is last summer’s CrowdStrike incident, which caused the operating system of a major provider to crash, displaying the so-called blue screen of death. This led to significant disruptions across sectors, including banks.

Lastly, we can also see that the number of significant cyber incidents reported to the ECB more than doubled between 2022 and 2024.

Chart 5

Number of significant cyber incidents reported to the ECB by significant banks

Source: ECB Banking Supervision.

Worryingly, we see a clear increase in attacks on third-party providers to which banks have outsourced certain services. Let me be clear: there are very good reasons for banks to outsource certain activities. For example, if they want to take advantage of cost efficiencies, or be more agile and optimise their own resources and expertise.[10] However, as the rising number of cyber incidents highlights, outsourcing also comes with risks that banks should assess thoroughly to ensure business continuity. Considering that European banks are highly dependent on third-party providers, particular vigilance is needed, especially in times of rapid geopolitical change. Banks may want to consider revisiting past risk management decisions when (re-)assessing their outsourcing arrangements.

Chart 6

Overview of type and number of significant cyber incidents reported to the ECB by significant banks

Source: ECB Banking Supervision.

Note: ”(D)DoS” stands for “(Distributed) denial of service”.

The examples that I just mentioned illustrate a fundamental point: in times of increasing digitalisation and geopolitical tensions which are fuelling cyberattacks, operational resilience is more important than ever.

However, unlike financial resilience, operational resilience can’t be built up by accumulating Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1). Instead, boosting operational resilience requires investment. Given the current rise in banks’ profitability, the time is right to continue investing in operational resilience. The more banks invest with strategic foresight, the better they will be operationally prepared if and when a cyberattack hits, for example.

Moreover, the Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA), which became applicable in the EU earlier this year, will help to further boost operational resilience as it provides a robust framework that requires banks to foster a culture of continuous IT and cyber risk management.[11]

What’s more, neither cyber risks nor other risks stop at borders. Given the interconnectedness of the international financial system, international cooperation is vitally important. The good news is that we have well-established existing global institutions and fora such as the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the Financial Stability Board and the Central Banks and Supervisors Network for Greening the Financial System, which remain essential for financial stability, especially in the current risk context.

Hence, as we navigate through a complex risk environment with heightened uncertainties, vigilance, prudence and resilience are more important than ever. But resilience – whether financial or operational – isn’t just about protecting banks from shocks. It’s also a foundation for long-term competitiveness. A bank that is robust in times of crisis is also a bank that is robust at all times so that it can invest and compete to the benefit households and firms.

Competitiveness and financial sector resilience are closely interlinked

And this brings us to a broader question in the debate on competitiveness: how does one ensure a strong and competitive banking sector without compromising financial stability?

Let me be clear: framing financial stability and competitiveness as opposing forces is a fundamental misconception. Evidence shows that stronger, better capitalised banks are more competitive and – most importantly – better equipped to lend to the real economy.[12] Impact assessments of the post-crisis reforms in the banking sector show that the benefits clearly outweigh any potential unintended side effects.[13] Hence, competitiveness and financial sector resilience are closely interlinked. Neither can exist without the other.

Having said that, we generally support simplifying the regulatory framework where possible, as long as the current level of resilience of the banking sector is maintained and any changes are based on prior, sound impact assessments and cost-benefit analyses. After all, if we all agree that it only makes sense to legislate after solid ex ante impact assessments and sound analyses show that the benefits of certain rules outweigh their costs, then it must make just as much sense to rigorously perform these same assessments and analyses before scrapping those very same rules.

We must ensure that any short-term gains in simplification do not actually result in any long-term loss of resilience prudently built up over the last decade. We also need to ensure that simplification efforts do not leave pockets of risk unaddressed.

Let me illustrate this with an example. As prudential supervisors, our true north is that no material risk remains unaddressed. An important precondition for banks to be able to prudently manage their risks is that they have accurate risk data and information from their customers. The financial risks stemming from the ongoing climate and nature crises are no exception to that principle. It is therefore vitally important that any attempts to simplify sustainability reporting for companies do not result in critically important data points needed by banks to adequately manage their climate and nature-related risks no longer being disclosed in a harmonised manner. If this were to happen, banks would either no longer be able to conduct adequate risk management, or they would have to resort to requiring additional data from their clients on top of the current regulatory regime, which would be burdensome both for banks and their clients.

The economist Hyman Minsky wisely stated that, as memories of past crises fade, attitudes towards regulation change. Let me add that if such attitudes lead to confusing simplification and deregulation, memories of past crises could return with a vengeance.

The last thing we should do, especially as we go through times of high uncertainty, is to let our guard down as regards resilience and hamper banks’ ability to manage their risks, thinking that “this time will be different’’, the phrase so poignantly coined in Rogoff’s and Reinhard’s “Eight Centuries of Financial Folly”.[14] Let us, for once, avoid such folly and sidestep that all-too-attractive trap.

Instead, let me point to an often overlooked yet crucially important aspect that has significant simplification potential and does not come at the expense of resilience: a primary root cause of complexity in the European framework lies in the persistent fragmentation of rules at national level. For example, many facets of the current prudential framework do not actually consist of a single European regulation but of a patchwork of nationally transposed directives. To truly reduce complexity, we need more harmonisation at EU level through directly applicable regulations which would achieve a truly unified single rulebook. I would even go as far as to say that a more integrated and European approach is the most effective way forward to ensure that our regulatory framework is simpler and more effective. Financial markets would also greatly benefit from the harmonisation of corporate insolvency rules, accounting frameworks and securities laws, as well as from better disclosure of financial information by EU corporates. To make progress in these areas, alternatives methods could be envisaged, such as the introduction of a 28th regime, which would be a practical and very welcome intermediate step towards further harmonisation within the EU.

A completed banking union, including the establishment of a European deposit insurance scheme and a fully integrated capital markets union, would help eliminate barriers that still hinder market integration and would ensure that the financial system fosters both stability and growth. The path to greater competitiveness does not therefore lie in deregulation but in further European integration.

Moreover, as far as European banking supervision is concerned, we continuously apply a risk-based approach to simplify and reduce complexity and cost factors that unduly inhibit our task of keeping banks sound.

One example of our drive for “simplification without compromising resilience” is the comprehensive reform of our annual health check of banks, the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process, which we recently made leaner, more risk based and more efficient.

The recent, fast-track approval process for standardised securitisations is another excellent example of how, in close dialogue with the industry, processes can be simplified within the existing regulatory framework. By leveraging product standardisation for sufficiently simple significant risk transfer transactions, the fast-track process will lead to efficiency gains without – crucially – weakening our focus on relevant risks. I sincerely hope that together we can identify and pursue more initiatives of this kind.

We will also continue to reduce processing times by making better use of supervisory technology tools that use cutting-edge technologies, such as artificial intelligence. For example, since March 2023 we have been machine reading and pre-screening all our fit and proper applications, which speeds up supervisory assessments and, in turn, the responsiveness to banks.[15]

Conclusion

Let me conclude.

The progress made over the past decade has made European banks more resilient. Banks have evolved from shock propagators to shock absorbers.

As we navigate through the storms brewing over today’s increasingly complex risk landscape, stable banks are more important than ever.

Rolling back on safety and soundness would not only undermine financial stability but also weaken banks’ ability to finance the real economy.

Does that mean that there is no room for regulatory simplification? Does it mean that there is no room for any efficiency gains in the way we supervise? Of course not.

But let us stay on course while we explore how to simplify and harmonise the regulatory framework.

Let us stay on course while we continue to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of our supervision.

And let us stay on course in ensuring that the European banking system remains resilient.

Because resilient banks are nothing less than the bedrock of competitiveness and growth.

Thank you for your attention.

The reference date for data contained in this speech is the third quarter of 2024. As of 20 March 2025, data for the fourth quarter of 2024 can be found on the Supervisory data web page.

Previous systemic financial crises resulted in average output losses of 8.5% of GDP in EU countries. See Lo Duca, M. et al. (2017), “A new database for financial crises in European Countries’, Occasional Paper Series, No 194, July; and Woods, S. (2024), “Competing for growth”, speech at the Annual City Banquet, Mansion House, 17 October.

Strong profitability and a low cost-to-income ratio are important determinants of higher price-to-book ratios at individual bank level and hence banks’ attractiveness to investors. See “What is the outlook for the European banking sector?”, fireside chat between Kerstin af Jochnick, Member of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, and Chris Hallam, Managing Director at Goldman Sachs, at the Twenty-Eighth Annual European Financials Conference, hosted by Goldman Sachs in Madrid, 5 June 2024.

Chart 3 shows that banks’ own cost of equity estimates are at the lower end of our estimate range

See Elderson, F. (2025), Interview with Het Financieele Dagblad, ECB, 17 January; and ECB (2020), Guide on the supervisory approach to consolidation in the banking sector.

See Elderson, F. (2024), “Securing stability in an insecure environment: navigating a bottleneck environment”, speech at the University of Cyprus, Nicosia, 21 November.

Munich Re has found that the average damage from natural disasters over the past 30 years (corrected for inflation) is rising. It averaged USD 181 billion per year worldwide over the past 30 years, but USD 236 billion over the past ten years and USD 261 billion over the past five years, reaching USD 320 billion in 2024. See Munich Re (2025), “Climate change is showing its claws: The world is getting hotter, resulting in severe hurricanes, thunderstorms and floods”, 9 January.

See previous speeches and blog posts on governance, including ECB (2024), “Banks’ governance and risk culture a decade on: progress and shortcomings”, The Supervision Blog, 24 July; and Elderson, F. (2023), “’Treading softly yet boldly: how culture drives risk in banks and what supervisors can do about it’’, speech at the 10th Conference on the Banking Union organised by Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, the Institute for Law and Finance at Goethe University and the Center for Financial Studies, Frankfurt am Main, 19 September.

See Article 88(1) of the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD); and ECB (2024), Draft guide on governance and risk culture, July.

For example, more than 70% of significant banks outsource critical payment services, and more than half outsource some of their lending and investment services. See ECB (2024), “Rise in outsourcing calls for attention’’, Supervision Newsletter, 21 February.

See ECB (2025), “Operational resilience in the digital age”, The Supervision Blog, 17 January.

Budnik, K., Dimitrov, I., Gross, J., Lampe, M. and Volk, M. (2021), “Macroeconomic impact of Basel III finalisation on the euro area”, Macroprudential Bulletin, No 14, European Central Bank. See also Siciliani, P., Eccles, P., Netto, F., Vitello, E., Sivanathan, V. and van Hasselt, I. (2023), Paper 2: The links between prudential regulation, competitiveness and growth. Background working paper published by PRA staff in support of the conference on the role of financial regulation in international competitiveness and economic growth conference 2023, Bank of England Prudential Regulation Authority, 11 September. On the usability of buffers for bank lending, see Couaillier, C. et al. (2021), “Bank capital buffers and lending in the euro area during the pandemic”, Financial Stability Review, November; and Couaillier, C. et al. (2022), “Caution: do not cross! Capital buffers and lending in Covid-19 times”, Working Paper Series, No 2644, ECB, February.

Financial Stability Board (2025), Evaluation of the Effects of the G20 Financial Regulatory Reforms, 22 January. See also the overview of the evaluations performed to date.

Rogoff, K.S. and Reinhard, C.M. (2011), This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, Princeton University Press.

The ECB uses a dedicated tool called Heimdall, which is constantly updated and enhancements. For instance, we have further automatised the transfer of findings from fit and proper assessment to our core IT systems and in turn their timely communication to banks. Heimdall also supports a risk-based supervision approach as supervisors can now more easily focus on cases flagged as complex and at the same time speed up the assessment and conclusion of simpler cases. See ECB (2025), “Bridging the gap between people and technology”, interview with Alessandra Perrazzelli, Deputy Governor of the Banca d’Italia and Member of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, Supervision Newsletter, 19 February.

Bank Ċentrali Ewropew

Direttorat Ġenerali Komunikazzjoni

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, il-Ġermanja

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Ir-riproduzzjoni hija permessa sakemm jissemma s-sors.

Kuntatti għall-midja